American Sabbatical 101: 4/24/97

Tahlequah

4/24.. Talequah

Peggy doesn’t give up easily. She had her heart set on finding the end of the Trail of Tears,

so we set off from Salisaw . Not before making a ritual stop,

however. She’d visited a Cherokee Nation gift shop on our last

passage through, and had found it full of local beadwork. We’d

spent the night across the road from it, so...

Then on to Tahlequah, the Cherokee capitol. But which sites to

visit? To peruse the guides there were a dozen likely spots where

we might lay hands on the spirit of the place. We’d found history

in Oklahoma an elusive prey, however. Either every stone was historic,

or pieces of an old cabin were enshrined by mom and pop.

The country is a joy, though, so we meandered around Northeastern

Oklahoma. More rolling hills than mountains here, and the trees

less towering. You can sense the prairie province seeping in.

Lots of small scale agriculture here. Beef and ratites. Hard to

think of the Cherokee as ostrich breeders. Then again, those plumes

on the head dresses in the old paintings...

Our first stop was at Gore, where a council house and court house

had been preserved. Another family operation, with the flagstone

dwelling and outbuildings in a compound with the historic structures.

Maybe I should renovate my attitude. Here were all the signs of

seasonal pluralism, that mixed subsistence economy we’d been a

part of in the maritimes, and I remember how healthy it was to

change jobs through the seasons. Incorporating a bit of historic

preservation in the mix seems a shrew addition. Turns out this

is actually a Cherokee Nation site, and the caretaker produces

the local paper as well, but that doesn’t devalue my premise.

Why not enshrine and museumize part of your house, and put down

your tools when the tourists arrive? Where does local history

start and finish? Is there a different attitude toward history

here?

The map wasn’t clear about the route from Gore to Tahlequah, so

we Owled crosslots by compass. You get a different sense of environment

roaming the tertiaries. Winding up and down the backroads. Pulling

over to let the locals flash past. We were circumnavigating the

Tenkiller Reservoir, and there were the requisite boats on trailers

in the dooryards. What there weren’t were churches at ever crossroads.

A few “Ritual Centers”, but no Burma Shave scriptures exhorting

our holiness, or warning against our deviltry. I’d actually grown

fond of the fervid sanctimony, and looked forward to the next

obscure chapter and verse. “What shall I do with this Jesus they

call Christ?” But here there was only an occasional sign in Cherokee

script. Of course, they might be Bible quotes, too.

Peggy had weaned the list to two excitements in Tahlequah. The

Cherokee Heritage Center, where there is a tribal museum and a

preserved village, and the Murrell House, the only house to survive

the devastations of the Civil War. Well, the Heritage Center was

a bust. The Museum is closed. We looked in the windows, and it

looked a bit thin, in any case. An exhibit under construction

honoring a tribal elder was a display board of platitudes without

any grist. The village was a collection of turn-of-the-century

buildings from all over Oklahoma brought together in a twisted

grove of 50 foot hardwoods, just starting to leaf out. It was

strange coming into this hunkerdown grove out of the open sweep

of rolling country, and the village had absolutely no charge.

I still wonder what sparks the magic in these sites, or doesn’t.

I sketched the one building that caught my fancy, a small house

which had a hint of that verticality we’d admired in the Chucalissa

thatched houses and in the Cherokee buildings at New Echota. An

echo of a traditional esthetic? Perhaps.

(Memo #98)

Apr 24 The End of the Trail of Tears

WHO? Cherokee tribe

WHAT? Cherokee Courthouse and Council House, also Cherokee Heritage

Center

WHEN? after Cherokee Removal of 1830’s from southeastern USA

WHERE? eastern Oklahoma (Gore and Tahlequah)

HOW? historic sites and culture center to celebrate Cherokee history

TOPICS: Cherokee tribe, Trail of Tears, Native American history

QUESTIONS: What happened at the end of the Trail of Tears? |

Council House

|

Every bit of history you begin to investigate gets more and more

complex. There were really MANY trails of tears. The Cherokee

moved west in a number of stages at different times. There were

groups that migrated early and voluntarily to Arkansas (Sequoyah

among them) even before 1800 and established themselves there.

They were called the Western Cherokee (or Old Settlers) and later

in 1828-9 were removed from Arkansas to Indian Territory (Oklahoma).

Even the famous Trail of Tears that was (the forced removal of

the eastern Cherokee in 1838-39) occurred over several years and

used several routes and had stops and involved a number of migrating

groups. It is hard to get the whole picture.

I've wanted to tour the Indian areas of eastern Oklahoma for years,

to see what life was like AFTER the Trail of Tears. Our recent

travels in Georgia to the prehistoric mound sites and then to

the pre-Removal Cherokee sites made me even more eager, to see

the end of the trails. At New Echota, Georgia, we saw the incredible

government buildings the Cherokee had constructed for their new

democracy, the Council building, the Supreme Court, also the newspaper

office - all clapboard structures with steep pitched roofs, many

glass windows, well crafted furniture. We saw grand Cherokee mansions

(Vann house, Ridge house), and smaller farm homesteads. Would

things be physically the same in Oklahoma?

Guidebooks listed many Native American sites and things to see

in Oklahoma - remember that the Cherokee are only one of the tribes

"removed". There were also tribal areas for Choctaw, Chickasaws,

Creeks, Seminole and others. There are local museums and town

museums and private (mom and pop) museums and mission sites and

statues. We toured the prehistoric mound site at Spiro to see

the western edge of the Mississippian prehistoric culture.

With limited time we decided to go to Gore to see the Cherokee

Council buildings, then to the Cherokee Heritage Center at Tahlequah

(the major town of the Cherokee area) to see a reconstructed ancient

Cherokee village, a 1900 village, the Cherokee tribal museum.

The Gore site is on a hill right by the highway about thirty miles

southwest of Tahlequah. Named after the chief who lead the first

group west, it is called TAHLONTEESKEE (the Council ground of

the western Cherokee). The Western Cherokee reestablished their

tribal government at Gore and this was the Cherokee western capital

from 1829-39. Chief Tahlonteeskee was succeeded by John Jolly,

a friend of Sam Houston, who visited the Gore area. Houston had

run away from home to live with the Cherokee as a boy in Tennessee

and married one of John Jolly's daughters.

In 1839 the eastern Cherokee who survived the the Trail of Tears

arrived in Oklahoma. There was a struggle over government between

the eastern and western (Old Settler) groups. The Eastern Cherokee

under John Ross (who remained as Cherokee leader through the forced

Trail of Tears and into the 1860's) got control of Cherokee government

and moved the government to Tahlequah in 1843 where it still is

based. The factions came together in 1846 when the two leaders

(John Ross and Stand Watie) met to shake hands and ushered in

what is called the "Golden Age". This ended, tragically in the

Civil War. Cherokee served on both sides of the conflict and the

US government later used the tribe's "treason" as justification

for taking more land. The Murrell home in Tahlequah is the only

Cherokee house there to survive the Civil War.

|

Murrell House

|

At Gore, the three buildings are crowded into a small fenced area

between a rural road and the highway with a modern ranch house

(for the site supervisor) and a small gift shop abutting them.

The buildings are made of rough boards with a few windows (not

the grander clapboard construction of New Echota). Each has a

stone stoop and fireplace for heat. There is an original one and

a half story frontier home built in 1843 that was moved to the

site. The other two (the Court building and Council House) are

accurate replicas. Each is about thirty by forty feet square.

There are good benches and tables in each. Each has exhibit cases

on a variety of subjects - cases of stone arrowheads, old picture

from Cherokee history, maps of Indian Territory. There was a reproduction

of parts of the Cherokee "Laws of Old Settlers" (monogamy, women's

legal rights, conditions under which "accidental" death was forgiven,

establishment of Cherokee police). There was little text material

(brochures or labels) to make the buildings come alive. It seemed

a random collection of tribal memorabilia. Maybe this is why the

site had so little "charge" for me.

Cherokee House

We went on to Tahlequah through hill country, following the edge

of a series lakes. This areas has been built up as fishing resorts

and we saw many roadside signs for cabins and boats, jet skis

and bait. Also many planned communities.

Cherokee Court House

|

At Tahlequah we easily found the signs in to the heritage center

and had a real disappointment. The museum (in a lovely modern

stone and glass center) was closed as was the recreation of the

prehistoric village!! We could tour the 1900's "village", a collection

of historic buildings that have been moved to the site and gave

me the feel of a movie set (all smartly painted). There was a

one-room school, a church, a store, several houses from around

1900 in a rather crowded fenced site.

|

Near the Heritage center is the imposing white Murrell House,

the only Cherokee home in Tahlequah to survive the Civil war.

It is grand in the manner of the eastern Cherokee plantation houses

like Ridge home (The Chieftains) of Georgia. The homesteads and

houses shows how affluent and cultured the Cherokee were as agricultural

settlers, even on the frontier in Oklahoma. The present day Cherokee

government is housed in a large complex of modern brick buildings

on the edge of Tahlequah and were very busy on the day we visited.

Tahlequah is a large modern town with all the usual business you

find on a typical American strip - fast food and malls. The Cherokee

sites in Oklahoma did not equal those in Georgia for me, but I

find the rolling hills and rich woods of Oklahoma very beautiful.

Far from being plunked in a barren wilderness of grass (as I had

once thought), the Cherokee found a lovely lands at the end of

the hideous Trail of Tears (though it may never have equaled their

Georgia and the Carolina homes for them).

4/24.. cont.

Peggy had had enough. We photographed the Murrell House, now a

private residence, on our way out of town. We headed for Tulsa

and the Gilcrease Museum of Art.

Coming down out of the hills by stages. We’d cross expanses of

flatlands with widening vistas, then entangle in convolutions

again. We’d left the great woodlands behind and the trees were

more hunched and thickety, showing twisted habits, or leaning

away from prevailing winds. Lots of untilled pasturage here. Except

for the barbed wire, this could be the broken buffalo grounds

or the cattledrive ranges of old. Tahlequah calls itself the “Nursery

Center of America”, and long plastic greenhouses and rows of nursery

plantings and pot shrubs patterned the landscape here and there.

We’re back in early Spring again, with only hints of green in

the fields, still dominated by the somber khakis of winter straw.

And oil pumps, dipping and rising. The towns rawboned and muscular.

Very workaday places. Men in ballcaps driving pickups full of

welding rigs, flatbeds loaded with pipe. None of your squishy

politics here, I bet.

And the weather is catching up with us. Northeast gusts shoving

the Owl. The ceiling coming down. Bursts of rain. By the time

we get to Tulsa it’s coming down steady and we’re glad of an inside

visitation.

Tulsa is a full-sized burg, the first we’ve encountered since

the Big Easy. We even saw a Borders alongside the highway. And

it’s as sprawled as any suburban urge could wish. As we rolled

across the superhighwayed grid we kept looking for a highrise

downtown, and were fooled three times by miniclusters before we

spotted the tall shinys of the big brag. The Gilcrease Gallery

of American Art is another oil fortune collection perched on the

upside of town. That means high on the hills over the Arkansas

River.. above the suburban clamor.

A great collection. These privately endowed institutions have

a more laidback atmosphere. It’s all bought and paid for, we aren’t

trying to sell you anything. As usual I was knocked out by the

Remingtons, but there was a lot more here to bug your eyes. I’d

never seen a collection of Millers.. or even a mention of King.

King’s paintings were of Native Americans very early in the 19th

century, and were more interesting for their historic qualities

than for their technique. The Millers on the other hand were extremely

evocative studies of Indian faces, with none of the emphasis on

their exotica. DeVoto, in Across the Wide Missouri follows Miller’s

travels in the High West, and it was a thrill to see some of the

actual paintings.

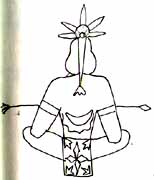

The 20th century sculpture of Willard Stone was what grabbed me

hardest at the Gilcrease. His stylized evocation of a Native mythos

felt just right. Not mawkish or condensed to logos, simply reduced

to the essential gesture. The wood spoke through the forms, and

the human truths as well. I’d smiled at the listing of Willard

Stone’s house and personal collection in the Oklahoma State guide.

Now I was sorry we’d missed it.

The guide had also been wrong about the hours at the Gilcrease,

saying it would be open late on Thursdays. Closing call came all

too soon. Before we could soak it in, and do sketches. Out we

went onto the rainy prairie. West of Tulsa you are definitely

in the West. We logged some more miles across the Great American

Desert, and finally came to rest in Stillwater.

(Memo #99)

Apr 22 Norton Museum and the Gilcrease Museum

Who? two arts patrons, Norton and Gilcrease

What? museums of (European and) American art

When? twentieth century

Where? Shreveport, LA. and Tulsa, OK.

How? collections by wealthy men

Topics: museums, western art, Remington collectors, patrons

Questions: What is western art? Should it be judged differently

from other art? |

Tree Dog

(After Willard Stone)

|

The Norton Museum is a lovely yellow brick building in its own

park in Shreveport. It is amazingly low key, in fact it is so

little advertised that it was difficult to find. Almost no signs.

There is no entrance fee and no reproductions of the art in postcards,

only art books. It has about ten galleries divided by style and

medium: glass in one and firearms in another. We focused on the

western and Hudson School galleries, the Remingtons, Bierstadts,

Durands.

|

The Gilcrease Museum is on a lovely hill on the western edge of

Tulsa with a vista of rolling hills from its lounges, and azaleas

all around. Its collection is American, from marble busts of the

founding fathers by Houdon to works by twentieth century Native

American artists. It also has a strong collection of Hudson School

artists, especially Thomas Moran. It has some real surprises too:

a watercolor by John Singer Sargent of marching soldiers on the

western front, impressionist scenes by Remington, sculpture by

twentieth century Oklahoma Native Americans. |

We toured both museums, in spite of advancing museumities, because

of the fame of their Western collections, especially works by

Remington and Catlin.

|

My husband and I are fans of Frederick Remington. The more we

look at his work, the better it becomes. His bronze sculptures

of cowboys are well known as are his painting of cowboy scenes.

Some people scorn him as an “illustrator”. True, his pictures

often tell stories vividly. But look carefully and you’ll see

the skill and the craftsmanship in a variety of media. He did

watercolor, gouache, oil, pencil, ink, sculpture. He uses impressionist

techniques and realism. Some of his paintings verge on photorealism.

Others - like a moonlit scene of Native American women butchering

a buffalo - have the feel of a Whistler night scene in London. |

Oceola

|

When we visited the Cody Center in Wyoming last fall and saw its

gallery of Western art we pondered the whole question of art v.

illustration. The Cody gallery tackled the issue this way:

|

“This type of art has sometimes been criticized as ‘merely’ illustration,

implying a lack of creativity on the part of the artist because

he did not necessarily originate the subject matter. Yet the best

illustrators can stand on their own as works of art. These

artists use the elements of art to make strong visual statements

while following a long tradition of storytelling through painting.”

|

|

At both the Norton and Gilcrease we saw works of art by Western

artists that can stand on their own.

Remington is represented at both museums by both two and three

dimensional art. He did some quite different black and white illustrations

of the Hiawatha story. One is called the “Famine Death of Minnehaha”

and has a spectral figure looming over her bed. Another pair of

small pictures is his representation of Paleolithic man and Paleolithic

woman (a bit more brutish than today’s reconstructions). I do

really love his night paintings, he caught moonlight with a pale

green light to each scene. The Norton has Remington’s first oil

done when he was 24. It IS exciting to see a lot of work by one

artist. Remington’s Native Americans are often lyric figures that

don’t seem maudlin to me. Remington’s oils often catch people

in a moment of reflection or pause - looking at clouds or reacting

to a death. His bronze statues, on the other hand are action shots

of bucking broncos, collisions between a buffalo and a rider,

groups of galloping horsemen. They are wonderfully intertwined

and massed. None is bigger than two or three feet wide and two

feet tall. Often the whole statue is poised on a horse’s leg or

a buffalo’s rear quarters. It is amazing to see the detail of

a man being violently thrown from a horse that is caught on a

buffalo’s horns. Occasionally the proportions seem a little off

or a movement bizarre, but then how many of a us have seen a man

being violently thrown from a horse caught on a buffalo’s horns?

Jackson

|

The other famous western artist represented at both museums is

Charles M.

Russell. His colors are vivid and his scenes realistic. There

is a great deal of detail to take in. And he paints most lovely

skies, evening skies and dawn skies and bright sun. Yet I find

his figures often verge on caricature and I don’t react to them

as strongly as Remington’s.

|

For both men, the “West’ is rolling grassland, sandy draws and

dry lands with stark mesas. Our travels have shown us a much wider

variety of western landscape - the lovely high meadows of Wyoming

and Idaho, the steep forested slopes, the variety of woods even

in western Oklahoma and Kansas. Navajo country has pinyon forests.

The Gilcrease had federal era portraits by Peale and Sully. Two

marble busts (of George Washington and John Calhoun) that catch

the men’s power and conviction.

There are delightful oils by George Catlin, including a hilarious

one of a huge prairie dog town. An unexpected portrait was of

a Cherokee chief by Sir Joshua Reynolds (painted in London or

America?). Wonderful pictures by Alfred Jacob Miller and Charles

Bird King. |

Calhoun

|

There were icons of American art at both museums, pictures that

are in every American history textbook: Penn’s Treaty with the

Indians, Walker’s scene of a cotton plantation, Remington’s Stampede,

Moran’s waterfalls, Biertadt’s Yosemite. There is a shock of recognition

before your eyes examine the works. You often find new colors.

The Hudson School paintings really are huge and the scale is extremely

effective. The viewer is drawn into the landscape. Moran’s huge

"Shoshone Falls" seems to fill the gallery with thunder and cool

spray. I found it mesmerizing.

Gilcrease was a patron of Native American artists in Oklahoma.

Three men in this century are extensively represented: Acee Be

Eagle, Woody Crumbo, Willard Stone. Each had art school training

and was part of the academic world. Eagle lectured on Indian Art

at Oxford. Each uses Native American subjects and symbols. There

are some portraits and some small scenes that have a distinctive

style - framing borders or symbols, highly detailed and formal,

precisely drawn, hardedge. Very two dimensional and colorful,

very visibly “Indian”. They almost seem like Persian miniatures.

Willard Stone does very beautiful wood carvings, curvilinear,

elongated, streamlined . The wood has been worked to a satin finish,

there are no hard edges at all. One piece has an intertwined couple

in which the woman’s cowl flows into the line of her arm and then

the man’s robe. Another is a long praying figure with bowed head

over elongated hands atop a flowing column of body.

The museums along with the one in Cody are a lovely representation

of Western art. And much more.