American Sabbatical 99: 4/22/97

Creole Country

4/22.. Creole Country.

Maybe it was the hot sauce. I had a rumpled night, full of anxious dreams. Tornadoes marching

along the horizon. Running out of gas on desolate roads. I was

just as glad to get up and face the lowery morning. Yesterday

evening Peggy shocked the Army Reservists camped out at the Ramada

with us by doing laps in the pool. They just shivered over their

beers. This morning I felt a bit shivery in my Elvis T-shirt,

but Peggy had another swim. I didn’t put on my jacket. Us Yankees

are tough.

| We were out of the Mississippi Valley now, going up the Red River

toward Shreveport, but it’s still bayou country. Down here in

the alluvium the rivers have changed channels time and again,

leaving rich black soil and isolated backwaters for the gators

to sun in. Old plantations appear along the way, left high and

dry, or inundated with swamplands, but the vegetation is slowly

transforming again. The evergreen oaks are less dominant, the

willowy leafage is giving way to broader leaves, and more upland

habits. We are climbing out of the delta. |

Louisiana Pecans

|

This morning’s ambition is the Kate Chopin House in Cloutierville,

and the low stratus is blackening with clumps of nimbus. Spatters

of rain. We hump up over a narrow bridge, look down onto a muddy

red waterway snaking between mudcoated woodlands, the trees daubed

shoulder-high. Down a sleepy sideroad, lined with modest brick

houses surrounded with beds of flowers, is the Chopin House.

(Memo #95)

Apr 22 Kate Chopin & Harriet Beecher Stowe

Who? two women writers of the 1800’s

What? Creole village where both may have gained “inspiration”

for their books

When? mid to late 1800’s

Where? the Cain River (formerly another “red” River)

How? sojourning in a rural Creole area

Topics: women writers, feminism, Kate Chopin, Creole culture,

abolitionism

Questions: What were women’s roles in Creole society? Where did

Kate Chopin and Harriet Beecher Stowe get their inspiration? Were

they rebels?

|

Kate Chopin at Home

|

Cloutierville is a village on a small river in north central Louisiana.

You turn off a secondary road, cross a small bridge, and are on

a main street with closed stores that show former affluence. The

village is a mile long with a church and graveyard, a store, many

houses, and the Bayou Folk Museum in a house where Kate Chopin

once lived.

Out of the closet

|

We use Kate Chopin’s turn of the century book The Awakening in

American Studies. It is a tale of a woman’s growing self-awareness,

feminist and quite modern. When I saw Kate Chopin’s house noted

in a guide book, I wanted very much to learn about her. There

is a village named Chopin near Cloutierville on the map and I

was curious.

|

The Chopin house is a Creole cottage begun in 1805 by the first

Monsieur Chopin, smaller but with the same plan as the grand plantations,

a middle class house that is imposing alongside its small neighbors.

It is white painted brick, with an outer staircase leading from

the ground level floor up to the veranda and the real house. There

are four large rooms, two with fireplaces, and two more rooms

where the back porch has been enclosed, a large unfinished attic.

The long shutters were blue. Unlike Laura Plantation, the house

sits hard by the road with a bare twenty feet of yard in front

and a grand live oak.

| Cloutierville apparently has long been home to three groups: Creoles,

Creoles of color, and blacks. They live side by side and worshipped

in the same church (sitting in three different sections). The

guide said that Jews had been welcomed in the village, but not

“Americans”. English was not spoke by many until the 1950’s. She

distinguished between Cajuns and Creoles. Cajuns, the descendants

of Canada’s Acadians transported by the British in the mid 1700s,

are more isolated, speak an antiquated French dialect and had

few financial resources. Creoles, she said, were cosmopolitan,

Louisiana’s elite, and spoke Parisian French. |

Chopin House 1997

|

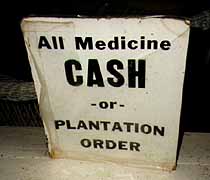

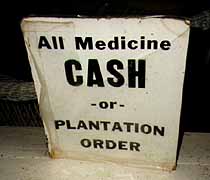

The Bayou Folk Museum is hodgepodge of memorabilia stuffed into

the house and yard. The charming doyenne told us that the lady

who had spearheaded it gave people basically forty-eight hours

to bring their treasures. There are World War 1 uniforms, old

wagons, a doll and doll bed collection, some wonderful pieces

from the old Catholic church that burned, grade school pictures,

kitchen utensils. Out back there is a dusty blacksmith shop and

a full doctor’s office in a two room cottage with rows of medicine

jars, prostheses, examining table and chairs. Fascinating! (He

was apparently one of the doctors who killed Kate Chopin’s husband

- more below).

KATE CHOPIN

Oscar

|

Kate Chopin is mainly represented in a case of memorabilia and

the EXTENSIVE knowledge of the guide. This was Chopin's husband’s

town, he is the Chopin whose family came from the area. Both Kate

and Oscar Chopin were (French-speaking) Creole (Kate from families

named Verdon and Sanguient, Oscar from Condes and Cloutiers),

but she was from one of St. Louis’ founding families. Her mother

had married an Irishman who was a financial genius and Kate was

born Katherine O’Flaherty in 1851. During the Civil War a half

brother died in a Union prisoner camp near Little Rock and Kate

was removed from her convent school for a year. She suffered the

first of the depressions that marked her life. Oscar was raised

in Cloutierville and was sent for bankers’ training to Uncle Benoit

in St. Louis where he met Kate. |

It was a whirlwind courtship. They married and went to Europe,

but their honeymoon was cut short by the Franco-Prussian War.

They lived in New Orleans for nine years and Kate became an ardent

feminist from influences in Europe and Louisiana. Kate and Oscar

had six children. Business problems in New Orleans and his father’s

death caused Oscar to move his family back to Cloutierville.

| “Cloutierville was not ready for Kate Chopin!” our guide declared.

She caused great controversy by her feminist habits: she crossed

her legs at the knee, drank BEER ( a man’s drink although women

were “allowed” to drink wine and champagne), smoked Cuban cigars,

and raised the skirts of her flamboyant Paris wardrobe when she

went up the street exposing her ankles and lower legs!! All the

men downtown would go out to watch Kate pass. Cloutierville mothers

felt they had to shelter their daughters from her influence and

Oscar’s sister told him to “get that woman under control!” Oscar

apparently approved of his sophisticated liberated wife. They

had a romantic marriage (which I didn’t suspect knowing the book,

the guide says that’s a common misperception). Unfortunately Oscar

died in 1882 of “swamp fever” when he and the doctors decided

to attack it with four times the usual dosage of quinine! Kate

was a widow at 31 with six children under 12! |

Kate

|

Cloutierville had a strict set of rules for widows. “It was time

for Kate to clean up her act!” It was expected that she would

turn her property over to the eldest male Chopin to manage; she

didn’t. She managed her own property. The village, according to

our informant, was “watching and waiting”! And Kate became “involved”

with a man who owned adjoining property. Our guide says no one

knows the extent of the relationship. The society was so strict

that she may simply have been seen talking to him alone (a taboo

for a Creole woman of any age). Gossip increased and Kate moved

her young family back to St. Louis. Oscar was exhumed and moved

too. She had been in Cloutierville perhaps five years.

|

When she was in her mid thirties, Kate lost her mother and went

into a depression. Her doctor suggested that writing was good

therapy. Her short stories, many set in Cloutierville, were an

instant success and appeared in all the popular journals. Two

collections of stories sold well. She also composed music and

lyrics (the display case held the sheet music for the “Silk Polka”

and “The Joy of Spring”). She was financially independent. |

Her 1899 book, The Awakening, “did her in,” said our guide. It

was banned in most cities (St.Louis was first!) and her third

collection of stories went unpublished. There was so much opposition

that Kate wrote an apology of sorts. Our guide smiled as she told

us that Kate’s “apology” in a literary newsletter said that “she

had had no idea her character was to misbehave so badly”! Typical

Kate apparently. She died in obscurity in 1904.

| In 1965 the village decided they’d “better do something for the

hussy who put it on the map.” There are her books and pictures

of Kate and Oscar and the children and a fascinating scrapbook

(invoices for cotton bales that Oscar signed, his doctor’s notes,

his will, Kate’s petition to be “Tutrix’ for her minor children).

A Kate Chopin trove.There are also quotes from her stories that

describe “Cloutierville.” |

Artificial Limbs

|

|

One says: “They lived quite at the end of this little French village, which

was simply two long rows of very old frame house, facing each

other across a dusty roadway." |

|

HARRIET BEECHER STOWE

Going through the dusty scrapbooks in the museum, I came upon

the Harriet Beecher Stowe controversy. Apparently there are many

people who believe that Uncle Tom’s Cabin is based on locals here

in Cloutierville. There WAS a slave named Thomas whose grave was

marked. And a Mr. McAlpin hereabouts who is said to be the model

for evil Simon Legree. Did Harriet Beecher Stowe really, as claimed

in one quote from her, get the stories from her brother who worked

in New Orleans? Did HE come to the Cloutierville area? Or did

she herself come up the nearby river by steamboat and get stuck

and stay at a local plantation as some claim? Or was it all promotion

to catch tourists? A cabin said to have belonged to the local

Thomas was taken to the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. It never came

back and may even have been sold off in pieces to the gullible.

(I love these peripatetic icons - TR’s western cabin also went

east for several fairs and is now happily set at a site 7 miles

from its original place! See what happened to Sequoyah’s cabin

in the Memo #97 !! ) None of the Uncle Tom artifacts remain, the

gravesite and McAlpin plantation are now privately owned. A neat

tie for me between Cloutierville, Louisiana, and Brunswick, Maine,

near us, where Mrs. Stowe actually wrote the book.

Bayou Artifacts

4/22.. cont.

The Chopin House is a one woman operation, and “Amanda” was a goldmine of lore

and lies, who would wink when she saw your jaw drop. Someone should

video HER act for posterity. All the while the heady scent of

rising bread floated into the “museum” from her house nextdoor.

It was airy and cool in the “basement” of the house, 18 inch thick

brick walls standing on the ground, cut by large shuttered French

doors, open fore and aft. Rain now pounding down outside. The

“house” itself was on the second and third floors. Our guide said

the basement had often housed sick animals, or been storage for

farm equipment. I’d just deduced that Southern houses were up

on blocks to avoid flooding, but Amanda set me straight. For the

cooling draughts, she said, and the termites. We had seen more

exterminating ad billboards than seemed plausible. REBEL EXTERMINATORS.

Suddenly the prevalence of middleclass brick in Dixie made sense.

Back in the plantation days the upstairs “house” might be made

entirely of wood. This old house would be a pleasure to live in,

with an upstairs gallery all round under the low-sloped eaves.

We’ve been asking after bakeries all through the South, without

much luck, and Cloutierville was no exception. But we were told

that Mrs. Ruby’s down the road had “the best crawfish pies you

ever tasted.” I think they still feel the old way about “Americans”

down here. The pies weren’t on the chalkboard menu, nor was their

price, and Mrs. Ruby herself hovered over us, saying she wasn’t

quite sure if she hadn’t mixed up the meat pies and the crawfish,

and wanted us to try them for her. The contents were so fine ground

and so spicy all you could do was inhale sharply and nod your

head. Big pitchers of sweetened tea sat on every table, and Mrs.

Ruby brought us glasses full of ice repeatedly.

Good nuts, though

|

Everywhere we’ve been in Louisiana people get farther into our

personal space than us chilly northrons are used to. I’ll play

any game, and tend to move closer still, but nobody backs off.

At Mrs. Ruby’s I began to wonder if the propinquity wasn’t to

pick your pocket. Everyone was smiling broadly when we pushed

out through the screen door, smoke curling out of our ears, $13

lighter. We laughed half the way to Natchitoches. |

Natchitoches. (Nak-a-tish.) Oldest settlement in the Louisiana

Purchase. A trading capitol up the Red River before New Orleans

had a shed roof. Once as legendary a crossroads as Timbuktu, now

a small city in the Louisiana rain. We got stuck in a traffic

jam on its two main streets, and by the time we’d sorted it out

we were out the other side, having missed the Historic District.

If there was one. Falsefront brick stores, a groomed embankment,

and gridlock at 2PM, was all we saw.

A traffic jam along the Red River was wonderfully appropriate.

When Capt. Henry Miller Shreve showed up in 1833 there was an

ageold logjam in the river that stretched for 165 miles. It was

so overgrown that travelers and drovers regularly crossed the

river without knowing it. Like the Army Corps, he set at it with

explosives, blasting a channel from end to end in a year. The

jam immediately closed behind him. It took Shreve 5 years to clear

“The Great Raft”, and open the Red for navigation.

|

Flowers, too

|

It only took us a couple of hours to amble up the Red, through

sprouting fields of cotton and cane.. and nodding oil rigs. We

were entering the great petroleum fields of Northern Louisiana

and East Texas. When I hitched here in 64, I’d stayed with my

friend Andy, and we’d gone out to his family’s “place at the lake”

for a barbecue. I remembered sitting with a mint drink on the

veranda, watching a red sun set behind acres of reciprocating

oil pumps reflected in the water. “Isn’t it beautiful?” Andy’s

father had asked.

Approaching Shreveport the sky clamped down black and hail pounded

on Owl, bounced high off the pavement, and slowed traffic to a

crawl. Between assaults, the wind thrashed the trees, and nasty

turbulent cloud wrangles roiled around us. I remembered my twisted

dreams. When we got into the city it was a mess. Trees uprooted

or downed. Limbs scattered. Power out. Standing water everywhere.

There had been gusts of 140 mph here, and a cataract of rain.

Peggy..

|

The traffic was all jumbled, and so were we. The Owlers were searching

for the R.W.Norton Art Gallery, but we got lost in the upscale

burbs of a hail-stomped city. No signs, no clear map, it took

us three tries to round in on the critter.

|

..Sketches

|

Remington

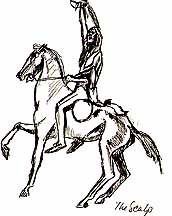

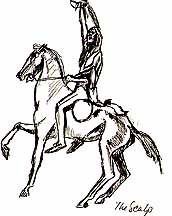

The Norton is oil money at work, noblesse obliging. A beautiful

building designed for exhibition of this collection, on immaculate

landscaped grounds, with a huge staff, and no hype, and no entrance

fee. We’d come to see the touted assemblage of Western art. Remington

and Russell in particular, and weren’t disappointed. The more

Remington I see, the more he is my master, in two dimensions.

Yeah, yeah.. cowboy pictures. But such craft, and power. And no

slouch at absorbing the modern techniques as they came along.

His later paintings are as impressionistic as any by the Parisian

tribe. After Remington, however, the rest of the Western genre

looks pretty weak. Russell can sure paint skies like a Montana

evening, but the master crosses the line from storytelling into

mythos, while Charlie Russell just spins a dandy yarn. Remington’s

bronzes don’t always work for me, though, mastery or no. He certainly

balanced the masses of men and horses in all their violent permutations,

but the dramatic excesses of his poses often overwhelm the haptic

feel of the pieces for me. That’s a perennial complaint against

“narrative” art. That the story detracts from feeling the visual

effects. I think that’s bunk. You can have a tale and poetry,

too. When the Remington magic works I’m galloped away. His action

groups ride a fine line between technical excess and choreography.

And sometimes they work best seen over your shoulder, across the

room.

We came back out into bright sunshine and puffy cumulus, sated.

And we didn’t even look at the Steuben glass, or Norton’s gun

collection.

| Now we’re trying to push our barge upriver as fast as we can,

so we raided a blacked out bakery for breads and buns, and gobbled

on toward Texarkana, next metropolis on the Red. I can’t pretend

to remember much of the jaunt through Ida, and Dodridge, and Fouke.

Except for Peggy’s sympathy toward a high school with the name

of the last of these. “Think of the chanting,” she mumbled. The

land was rising and rollicking more, and pine plantations were

pushing in among the field crops, but I was getting too dozy to

pay attention. We cranked up some Dixieland to bid the lowlands

adieu, and keep the driver awake. |

C.M.Russell

|

On the last long stretch between burgs I noticed the Owl’s gas

gauge was pegged out empty. Hadn’t heeded those dreams. THAT jarred

me awake, and we cruised into the outskirts of Texarkana on the

fumes. Found a road-dive just over the Texas line, and sang the

doggies to sleep.