American Sabbatical 90: 4/10/97

New Echota

4/10.. New Echota.

Brisk in the morning in North Georgia. No malingering in camp today. We chowed up,

mugged up, filed the thermos, broke camp, and wagged our tail

at Sloppy Floyd’s. Hanging out among the dogwood blossoms was

a lovely idea. Next idea.

We dodged the main drags as best we could, but we’re merging into

the industrial corridor of the South here, and even the blue highways

hum nonstop. Rolling through the valleys of the Chattahoochee

Forest and environs was green eye-therapy, with splashes of pink

and white dogwoods, and some luxurious purple-flowering tree I

can’t identify. Gentle backdrop hills framing fat lands. Wide

pastures full of slow cattle turning grass into groceries. Our

monkeyshines seem awful frantic next to Bessie.

We glided out of the pastoral into Calhoun, looking to find the

beginning of the Trail of Tears. It was just beyond the country

club golf course. New Echota (Ay-show-tah). Once the capitol of

the Cherokee Nation, and scene of one of our ignoblest hours as

a country.

If those ancient pyramids we’ve been visiting didn’t convince

you there was a native civilization here before Columbus, a visit

to New Echota will knock any lingering “primitive savage” notion

on the head. At least as regards the Cherokee here. The original

and reconstructed buildings on the old town site are masterworks

of the builder’s art, and the household effects were as sophisticated

as those in Lincoln’s New Salem, for example. Hearing “the Five

Civilized Tribes”, and reading descriptions of the Indian government,

newspaper, courts, and so forth, doesn’t match the impact of these

elegant structures. They have a four-square verticality unlike

any other Colonial era buildings. A mournful cultural pride, to

my overheated imagination. I found myself seething at the injustice

of Jackson’s removal all these ages later.

Cherokee Phoenix

(Memo #83)

THE STORY OF CHEROKEE MODERNIZATION AND THEIR REMOVAL OVER THE

TRAIL OF TEARS

|

April 9 Cherokee Heartland - New Echota

Who? Cherokee Tribe, leaders SEQUOYAH, John Ridge, James Vann,

John Ross

What? New Echota (Cherokee capital) + Vann House + Ridge House

+ Ross House

When? 18th and early 19th century

How? heartland where they adopted white ways and were still “removed”

Topics: Trail of Tears, Cherokee Indians, Indian Removal Policy

Questions: Why were the Cherokees removed? What was their homeland

like?

Why were they called "civilized"? If they were civilized, why

were they removed? |

Cherokee Council Building

|

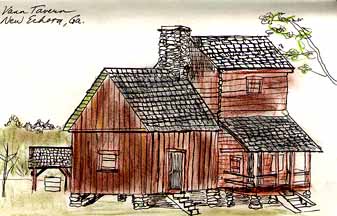

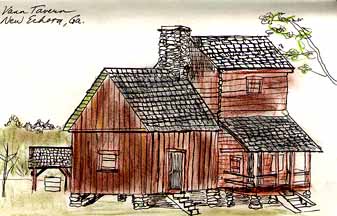

Vann Tavern

|

The Trail of Tears is a major focus of this trip, the forced removal

of perhaps 25,000 Native Americans from their heartland in the

Piedmont of the Carolinas and Georgia west to Oklahoma in the

1830’s. Their crime? Being Indian. Simple pure racism . The tour

of the Vann and Ridge and Ross houses and the Cherokee capital

of New Echota convince you of that. |

| Beautiful houses full of china and fine furniture, columns and

verandas and intricate moldings, the Cherokee Council building

with two chambers for elected representatives, the Cherokee Supreme

Court building with the places for judges and court reporter and

witnesses, the Cherokee Phoenix building which published a weekly

newspaper in both English and Cherokee. The facts of Cherokee

life before removal are visible. |

Courtroom

|

In the Pressroom

|

When English traders from Savannah and Charleston came to the

Cherokee in the late 1600’s and 1700’s they found villages of

hunter-agriculturalists scattered throughout the Piedmont. They

were descendants of the Mississippian townspeople who had built

the great earth mounds. They were organized into matrilineal clans,

the clans into towns, a number of towns into tribes, the tribes

loosely confederated. There were Cherokee villages in the Carolinas,

Georgia and Tennessee. The English wanted allies against the Spanish

further south and fought WITH the Cherokees on a number of occasions.

Many of the early traders married Cherokee women. Their children

became the culture brokers between the two groups, bringing white

man’s ways to the Cherokee, importing material goods as well as

ideas about architecture and government. Cherokee children were

sent north to be educated. The Cherokee welcomed missionaries.

The Cherokee - perhaps more than any other tribe - decided to

assimilate and adopted white culture as far as possible. The three

houses show their success. The best evidence of the success of

the Cherokee in assimilating is the title “the Five Civilized

Tribes” often given them (along with the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek,

and Seminole) |

As John Ridge said to a white audience in New York when he was

trying to mobilize white opposition to Cherokee removal, “You asked us to throw off the hunter and warrior state - we

did so. You asked us to form a representative government - we

did so. You asked us to cultivate the earth and learn the mechanical

arts - we did so. You asked us to cast aside our idols and worship

your God - we did so.” (1832)

| THE THREE HOUSES (Vann, Ridge, Ross). Georgia has instituted the

Chieftains Trail in the northwest part of the state which identifies

key Cherokee sites. John Ridge, James Vann, and John Ross were

all Cherokee leaders and men of substance in white terms. They

owned ferries and saw mills and plantation houses and slaves;

their three houses survive. |

John Ross House

|

We started our investigation of the Cherokee story, at the JOHN

RIDGE HOUSE (The Chieftains) in Rome, Georgia. It’s a large white

colonial house by a river, expanded from a roomy 1790’s log cabin.

Large gracious rooms are filled with rugs and fine furniture and

portraits of the families. The contemporary portraits show dignified

figures in rich white man’s clothes - the women in high necked

long sleeved dresses, the men in dark suits and ruffled stocks

with stern faces whose visible “Indianness” is a brown skin color.

Ridge House

|

John Ridge (1771-1839) built a fortune on agriculture and a ferry,

tavern, and trading post business. He owned over 280 acres (with

an orchard of 1134 peach trees, and 418 apple trees). He sent

his son John and nephew Elias to a missionary school nearby and

then north to a missionary run high school in western Connecticut.

The two young men, cultured and articulate (but nevertheless Cherokee),

began courting local girls in Connecticut and the town erupted.

The young men were burned in effigy and the school was closed!

The couples got married anyway and returned to northern Georgia.

Described by a Removal agent as “the great orator”, John Ridge

Sr. was a leader who represented the Cherokee in Washington. He

went on the Trail of Tears and was murdered as a traitor in Oklahoma

(see below). |

| The Vanns were even wealthier. The JAMES VANN HOUSE is a gracious

three story brick house with porches and white columns on a hill

near Chatsworth, Georgia. James Vann built the house in 1804.

In architecture and layout it is purely English, a large central

hall with a drawing room and diningroom on the first floor (and

a separate outside cookhouse), two large bed chambers each on

the second and third floors. There are twelve foot ceilings. A

few of the original furniture pieces remain, the moldings and

mantels, paint and wide board floors are all original. The son’s

violin is on display in a case. The showpiece of the house is

the cantilevered central stairway, the oldest surviving in the

state. The Cherokee features of the house are the paint and details.

The “Cherokee Rose” is represented as a carved medallion throughout

the house. The woodwork and moldings are painted in rather garish

tones of green, yellow, blue, red (representing grass, harvest,

sky, earth). |

Vann House

|

Vann Interior

|

Vann brought Moravian missionaries into the area, believing in

assimilation (though he himself was a polygamist!). The Moravian

influence is shown by wood details and the “Christian” doors (the

shape is said to resemble a cross and open Bible below). His son

Joseph inherited the family business and lived a more affluent

and assimilated life (with a single wife). The family owned 4000

acres and 110 slaves as well as a sawmill and tavern. Joseph raised

racehorses and died in an explosion on his steamboat on the Ohio

River. His brother David Vann went on the Trail of Tears and was

a direct ancestor of comedian Will Rogers.

|

| The JOHN ROSS HOUSE in Rossville (the original section of Chattanooga,

Tennessee) was built by John Ross’s grandfather the Scottish trader

John MacDonald in 1797. It is a large two storied log cabin (called

“dog trot”, a frontier style with an open walkway through the

middle). It has a deep veranda on the front and looked as though

it had six to eight rooms (it was closed until May 1). The Ross

fortune like the Vann’s and Ridge’s came from a plantation and

a ferry business. John Ross was only one eighth Cherokee but became

their strongest leader. Elected supreme chief under their representative

government and Constitution, he lead them for 57 years in Georgia,

on the Trail of Tears, and in Oklahoma. |

Ross's Dogtrot

|

Farmstead

|

The life of more ordinary Cherokees in the early 1800’s is shown

at the restored capital of New Echota in north central Georgia

which was laid out in English style streets around a central town

square where the government buildings were. There are two Cherokee

farmsteads, one a large two-roomed log cabin with barn, corn crib,

outbuildings. The other is smaller, a one-roomed log cabin with

small barn and corn crib. Both resemble frontier homesteads throughout

the region. |

MODERNIZATION AND REMOVAL - The story of the removal may begin

in 1802. The state of Georgia was being pressured by the federal

government to give up its claims to western land in Mississippi

and Alabama (remember the original colonial charter gave strips

of land between two Atlantic coastal points with indeterminate

western boundaries). Georgia signed a treaty relinquishing western

claims IF the federal government would remove all Indians. The

federal government agreed. Jefferson earlier stated that any Removal

was to be voluntary (“It may be regarded as certain that not a

foot of land will ever be taken from the Indians without their

consent “ 1786). The Creeks were the first tribe to be removed

west to Oklahoma and their last tribal lands were distributed

to whites by lottery in 1827

In the years after the 1802 Treaty the Cherokee assimilated, and

during the War of 1812 a number of Cherokee (including Ross and

Ridge, the latter rising to the rank of major) served under General

Andrew Jackson. They helped him win the key battle of Horseshoe

Bend against the Creeks. Ironically, Jackson was to be the President

who forced removal.

|

Indian Housing

|

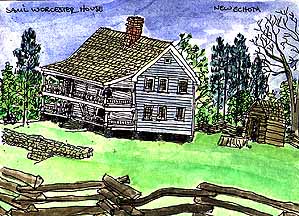

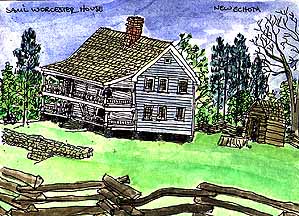

In an 1819 Treaty the Cherokee were given a section of northwest

Georgia. To demonstrate their progress, the Cherokee organized

a representative government and wrote a Constitution for the Cherokee

Nation, both patterned on the U.S. models. The capital of NEW

ECHOTA was laid out in 1819 near a mission established by Rev.

Samuel Worcester. Today visitors can tour the government buildings

and homesteads nearby. It has much the feel of Sturbridge Village,

Ma. or New Salem, Ill. Much of the town has disappeared.

Courthouse

|

There is the Supreme Court building, the Council (legislature),

and the newspaper. All are painted clapboard structures with many

glass windows. Inside there are well carpentered benches, platforms,

tables and chairs. |

| The newspaper is an astounding story. SEQUOYAH (or “George Guess”)

was a Cherokee who, although illiterate himself and with no working

knowledge of English, understood the value of written language

and documents. He set out to develop a form of written Cherokee.

It took him twelve years, but his 86 character alphabet was so

effective that the tribe became literate in a decade! The Cherokee

leaders procured a press with Cherokee and English type. The print

shop at New Echota produced over 733,800 pages! It produced a

Bible, hymnals, law and pamphlets in Cherokee and the PHOENIX

(the weekly newspaper printed in both Cherokee and English). The

symbol of the phoenix was chosen to symbolize the Cherokee’s ability

to rise above white stereotypes of Indians! |

Phoenix Building

|

So by the late 1820’s you had a group of Christian literate Native

Americans with an organized representative government and settled

agricultural way of life. What happened?

The Removal seems the result of greed, envy, and racism. The very

wealth that showed Cherokee success was resented by white frontiersmen

(the state of Georgia as part of the Removal held a lottery for

Cherokee land and improvements and white interlopers moved right

into the Vann, Ridge, Ross houses). In 1828 the discovery of gold

in northern Georgia lead to the first gold rush. Whites poured

into Cherokee territory and the state and federal officials did

nothing. The Cherokees strengthened their opposition and passed

a law in 1828 mandating death for any Cherokee who sold land without

tribal consent.

It is fascinating to see the LEGAL steps to removal. The federal

government had given the Cherokees rights and land under various

treaties, the state of Georgia set out to destroy them. A series

of discriminatory laws was passed (for ex. Cherokees could not

HIRE whites). The Georgia legislature abolished the Cherokee government.

and required all missionaries to have special licenses. Rev. Samuel

Worcester took the state to court in a test case of Cherokee survival.

Worcester v. Georgia went all the way to the US Supreme Court.

The Court (under John Marshall) found IN FAVOR of the Cherokees.

The Cherokee leaders felt vindicated. However, President Jackson

commented, “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce

it!” The president (who is labeled an “Indian hater” in history

books) supported the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The tribal leaders

objected, traveled to Washington and to New York to gain support.

It became clear that Jackson would send in federal troops to effect

removal.

The tribe developed two factions: those adamantly against removal,

and those who saw the future and decided to move voluntarily while

they still have some options.

A group of Cherokee leaders (without tribal legislature consent)

signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835 which gave up their Georgia

land. The President now had the

”legal” right to oust the Cherokee. Signer John Ridge said, “I

have signed my death warrant!” He was right. After the Removal,

signers John Ridge, his son John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot were

assassinated in Oklahoma on the same night by organized groups

of Cherokees acting under their 1828 law.

The U.S.Army (7,000 strong) moved in and forced Removal began

on May 26, 1838. Cherokees were literally seized in their fields

and at their dinner tables. Some were moved out with only the

clothes on their backs. Many houses, crops, businesses were burned.

15,000 Cherokees were concentrated into 11 stockades. The first

detachments sent on their trail of tears in hot weather suffered

many casualties. Hoping to stave off a total disaster, Chief John

Ross asked for a delay to cooler weather. It was granted. Ross

picked Cherokee leaders for 13 detachments who moved out under

Army guard for Oklahoma. They moved by foot, boat, wagon. The

routes took them north through Tennessee then across Missouri

and Arkansas to eastern Oklahoma. The trip averaged 116 days.

It is estimated that 4,000 people died on the Trail of Tears (including

Quatie Ross, John Ross’ wife).

|

“Murder is murder and someone must answer..Someone must explain

the 4,000 silent graves that mark the trail of the Cherokees to

their exile. I wish I could forget it all, but the picture of

645 wagons lumbering over the frozen ground with their cargo of

suffering humanity still lingers in my memory” - US Army Private John Burnett

|

|

We will follow section of the Trail of Tears west and will visit

the Cherokee lands in Oklahoma and, hopefully, the homes of John

Ross, Rev. Samuel Worcester, and Sequoyah there.

4/10.. cont.

We lingered at New Echotah, sketching and stretching in the sun. We keep swearing we’ll

slow down. Hang out. Sink into a place. But the road suction pops

us back into the red beast, and we roll on.

|

Cherokee Birdhouses

|

The movie in the windshield is starting to blur. The titled planes

of the rising Appalachians look like Vermont here, Pennsylvania

there, the backroads near home. We are firmly back in May now,

working the window crank to keep the riders happy. And keep getting

lost. Either we’re losing it, or the Georgia maps and signpost

simply don’t make sense. Short hops to historic sites make for

endless go rounds, and, quite frankly, the backsides of Georgia

towns look like the scene of the crime anywhere.

Eventually we found the Vann House, another of Peggy’s ambitions.

He was a wealthy slave-owning Cherokee, pictures of whose mansion

have been the most effective teaching aids in illustrating the

Cherokee Removal. I hung out with the Georgia storytellers again

while Peggy admired the lurid paint job inside. I was tickled

to think that this loquacious log, with its diversions and side

roads, mimics the form of the classic comic yarn. There isn’t

much point to it, the fun’s in the getting there. Hope nobody’s

waiting for a punchline. Punchy, is what we’re getting. We struggled

crosslots toward Chattanooga, but didn’t quite make it. Ringold.

Hope we don’t have Wagnerian nightmares. Goodnight.