American Sabbatical 108: 5/10/97

Blue Ridges

5/10.. Virginia.

We’ve got our road rituals perfected now. The morning assemblage and departure. The daily

Owl vetting. Plotting the navigation. Finding roadfood. The tour.

The sketch. The hooting at wrong turns or unclear maps and signs.

The laughter over another day’s absurdities. The quest for lodging.

Waiting for Homer.

Now we are going through the motions with cruise control on. The

Virginia Mountains in Spring are especially beautiful, and they

are like heroic musak for us. When we open out and hear it, we

are moved, but mostly we’re riding the elevator. Going home.

|

The Ridges

|

We rode the crest of the mountains from Roanoke to Charlottesville,

up on the Blueridge Parkway. Spring is recapitulated top to bottom

out here. On the high ridges, above 3000 feet, the trees are barely

in bud. Hunched, snarly things, mostly oaks and ash at a guess,

judging by the barks and limbs. There appears to be a lot of standing

deadwood up here, but that may be a comparative allusion, because

the limbs are so bare. We have noticed stretches of Pennsylvania

mountainside in late summer where the trees aren’t in leaf, in

recent years, however. Is there a niche die-off in progress?

Looking Downslope

|

Downslope the trees get taller, straighter, and proceed from first

leaves to full spread as you descend into the warm moist valleys.

By the time you hit bottom the variety of species is overwhelming.

The great temperate woods of Eastern North America, one of Nature’s

masterworks. I’ve religiously avoided woodyards and such lumbered

temptations this trip. Owl is having trouble with the upgrades

as is. But in another life I’ll roam these hills in a pickup,

with a chainsaw. |

Wildflowers are everywhere, at all altitudes, in all shades. Even

the windswept and chill crests are carpeted in tiny glories. Acres

of pink lady-slippers. Miles of purples and pinks and starred

whites. Violets under every tree. The dogwoods are making their

white and pink and yellow explosions in the higher woods. Laurel

are just opening lower down. Purple-flowered Paulonia are abundant

near the river bottoms.

Peggy's Vista

The vistas are compelling. Western in their sweep, if more humid

and rounded in contour. Heart-liftingly grand. Blue ridges, indeed.

Often seried into the diminishing distance. On the east slopes

of the Appalachians the spring leaves are all in shades of green-bronze.

The hills have a golden sheen, from almost yellow down to a keylime

green. The coloring follows the topography, with the crests outlined

in polished bronze against the valley greens. The Parkway often

skirts a cliff-edge, and you are looking down on the lesser Appalachia

and out to the farthest heights. The sensuous folding and articulation

is balletic, and you can understand Copeland’s inspiration to

the dance.

| Looking down into the fertile valleys west of Charlottesville,

not densely settled to this day, you have to wonder at the forces

driving Boone and the other Westerers. This country lives up to

its name, and the longing to see overhill would have to be fabulously

compelling to drive people beyond this Virginia. |

Blue Ridgers

|

On Saturday we came down off the heights to tour Cyrus McCormick’s

farm, west of the Blue Ridge Parkway. The road dropped 2000 feet

in a couple of miles, and was almost as knucklewhite as California

mountain descents. At least the Californians respect your intelligence.

Everywhere else, where the signs say 20 MPH you can do 30 in comfort.

When it says 20 in California, you better. This joyride had us

centrifuging at 25.

(Memo #105)

May 10 Cyrus McCormick

Who? inventor of agricultural machinery, industrialist

What? mechanical reaper

When? 1831

Where? western Virginia

How? his own blacksmith / carpentry training + a tinkerer father

Topics: inventors, agricultural history, farm machinery mechanization

Questions: What inventions affect us the most? What was the impact

of McCormick’s reaper?

|

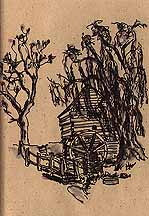

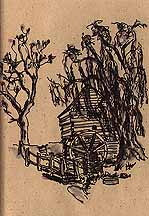

McCormick's Mill

|

I remember heated discussions in school of the world’s greatest

inventions. Fire? The printing press? Penicillin? Cyrus McCormick

is credited by some with creating the greatest invention of the

19th century. His reaper made it possible to cut farm labor drastically

(specifically in harvesting). He began the mechanical revolution

in farm machinery which has reduced the percentage of our population

required to raise food from 90% in 1800 to about 3% today.

Mac's Place

|

Walnut Grove (the McCormick place at the foot of the Blue Ridge

mountains in west central Virginia) shows the influences behind

the invention. The farm is in rolling farmland, rich wheat growing

territory in the early 1800s. There is a forge and a grist mill.

McCormick’s father Robert made his living as a miller and blacksmith

and was a tinkerer, determined to create inventions to increase

farm efficiency. He had experimented with reapers, but never made

an effective model. Acquiring skill with wood and metal, Cyrus

also focused on improving harvesting methods. |

Cyrus McCormick first invented a lightened scythe (the tool used

for cutting wheat). Then in 1831 he demonstrated the first horse

drawn mechanical reaper. It was made almost entirely of wood.

A wide horizontal blade towed behind a horse cut the wheat which

fell behind the blade on to a low and wide wooden platform. A

raker would walk alongside pulling the cut grain off the platform.

The McCormicks did two public exhibitions with their new reaper.

They showed that two men using the scythe (one driving and one

raking) could harvest six acres in one half day (an amount that

normally required a full day for five men with scythes)!

| McCormick made the first 100 reapers in his blacksmith shop at

Walnut Grove and sold them for $12.50 apiece. He then moved to

Chicago and started the first farm machinery factory. This was

the origin of his company, International Harvester, which became

the world’s largest producer of farm machinery. The McCormick

machines helped open the Great Plains. McCormick kept improving

the reaper (a seat for the raker, then an automatic raker, then

a cord binder - a simplified baler). He made a huge fortune and

accumulated many honors. He instituted new business practices:

machine performance guarantees, easy credit terms for farmers,

slick advertising. |

Early Reaper

|

The Walnut Grove site presents the story simply and effectively.

The forge and grist mill are preserved, two simple “cabins” with

two stories each, down the hill from the large brick farmhouse.

The forge is in the basement of one cabin with Cyrus McCormick’s

own tools still in place. The upper floor has a replica of the

first reaper, a large case with 14 scale models of McCormick machines,

and large photos of farmers and McCormick machines at work around

the world. One photo shows farmers in India cutting wheat with

small hand sickles. Another photo shows the first horse drawn

reaper with human raker alongside. Native American and Third World

farmers work with different McCormick reapers today.

Another view

|

Walnut Groves is still a working farm, now called the Shenandoah

Valley Agricultural Research and extension Center. Faculty and

students work on agricultural improvements here. |

As we drove across the Great Plains we would see lines of colorful

farm machinery in front of dealerships in every town (huge combines

with air conditioned cabs fifteen feet above the ground and gigantic

tires, tractors and a gazillion intricate attachments for breaking

soil, fertilizing, seeding, weeding, reaping, baling, loading,

moving grain). In December in Arkansas we saw huge combines working

at night by powerful headlights. In the spring we see the dust

plumes behind the huge contraptions that break soil in twenty

foot swaths from Louisiana to New York state. All the machines

that revolutionized farming are the offspring of McCormick’s mechanical

reaper.

5/10.. cont.

We hairpinned our way back onto the ridge and enjoyed sunshowers breaking through the

western clouds. Rode the high ground, gawping at the grandeur,

until Charlottesville hove over the horizon, then plunged into

the populous stews.

Bryce's Blue Ridge

Charlottesville is another kettle of fish. We're in the heartland

of Virginia Society here and the noses are eversoslightly elevated.

Manses, big and small, dot the swells, with the Blue Ridges behind.

Peggy wants to see Jefferson’s buildings at the University of

Virginia, so we climb that hill above town, and enter an elite

atmosphere. A wedding was in progress, and the institutional signs

and traffic cops indicate that this is part of UVa’s social function.

The wedding party looked grand, indeed, on the lawn before the

chapel.

There was no near parking for us hoi polloi, however. We cruised

round and about admiring the NO signs, until we found a way into

the inner sanctum of the main quad and parked in some professor’s

perkhole. “Do you suppose Sandy is in?” Peggy said loudly as we

unfolded. A dozen steps up from the Owl and we were within the

hallowed quadrangle.

Tom’s dome-on-a-temple sits at the top of the long sloping lawn,

which is completely enclosed by single-story red-brick residences,

pierced by brick archways, and punctuated by Greek pillar-and-portico

facades every dozen doorways or so. With mature shade trees overshadowing

patches of the quad, this is an idyllic enclave, out of the wind

and weather. It has all the feeling of cloistered condescension

that the BEST colleges strive for, compounded by being a walled

courtyard. A cathedral close for the Temple of Learning. Peggy

reported the same claustrophobia she gets in Harvard Yard. I though

it rather Brit for that old Francophile to have designed.

I know, I know. This is one of our architectural treasures as

a civilization, but what’s the message here? Elite faculty and

students get to have their brass nameplates on their private rooms

opening onto the lawn of exclusivity. The slave quarters are down

the hill. Not a person of color visible anywhere. I take it back.

There was a black sweeping the street at a lower reach of the

University. This is the least integrated part of the South we’ve

seen. Keeping up a noble tradition. OLLIE FOR SENATE, read the

bumperstickers.

The Owl glided down from the height, and lit in a back alley opening

onto a pedestrian mall in the middle of Charlottesville. Eye-easing

old brick shops and restaurants, cafes and bookstores. Noticeably

more integrated than UVa, but the blacks all in service roles.

Maybe a Saturday sample gives a skewed impression. Our veggie

meal was toothsome, and our postprandial stretched a tendon or

two. The sun had finally decided to stay out, and a westerly was

shaking the trees. We found a dosshouse out by the interstate

and played tag with Homer.