American Sabbatical 105: 5/4/97

Thomas Hart Benton

5/4.. Kansas City.

St. Joe on a Sunday morning, and I’m revving the Owl. The motel manager followed me out into

the lot.. is writing down our license number. Peggy does all the

dickering and sign in. As a result the lobby staff often does

a double-take when I wander through, or get the complementary

coffee. I keep hoping they’ll call the cops.

Breakfast is problematic, however. We suffered all night from

the fried chicken we ate in Hamburg, Iowa: the “Morel-picking

Capitol of America.” Everyone in the Country and Western Diner

was wearing a MUSHROOMIN’ T-shirt, but morels weren’t on the menu.

Hamburgers were, of course. We did chicken. This morning it’s

still doing us, and we can’t face any roadside food.

Last night we called the Evanses in Salem, Oregon. They used to

live in Kansas City, and gave us a list of sites to see, and their

favorite eateries. We figured we wouldn’t gnaw on each other too

much before we got there, so we cinched up and headed downriver.

It’s T-shirt weather again. I’m wearing THE KING. Wonder what

kind of luck that brings. Springtime in Memphis? Balmy sunshine

in Missouri, at least. The glowing green landscape soothes away

our road-wearies. After all the miles, here is the perfect Spring

day, at last.

On the outskirts of KC is another suburban agglomeration of inflated

edifices. I have to admit some of these 90s buildings are attractive.

Compared to Levittown bungalows, or the split-levels of the 50s

and 60s, the architecture is almost graceful. We’ve seen other

recent burgher palaces around the country that make us giggle.

Three-story capes, Neo-Georgian macrosurdities, Greek-resuscitation

Moderne. One sub-division in Basking Ridge, New Jersey, looked

like someone had hooked air pumps to the dream suburb of our childhood,

and blown it up to triple scale. On tiny plots. The new Heartland

haciendas have interlocking peaks and gables, rising up like little

mountains. Clustered tightly together, they make sawtooth figures

up the hillsides. Preposterously grandiose, the combined effect

is of a thousands peaks clustered for the alpine altitude convention.

We came down into the old city and crossed onto the south bank

of the Big Muddy. Another collection of nondescript bridges, from

our vantage, but there are seven crossings here, so we may have

missed a splendid synapse. It’s hard to get your directions straight

in Kansas City. The Missouri runs west from St. Louis to here,

then takes a hard turn north, toward Omaha. That made this the

logical jump-off for wagontrain emigrants. Steamboat navigation

higher upriver gets more uncertain, or did in those days, before

the Army Corps had their way. And, as we can attest, a more northerly

trajectory can be less salubrious. This is the season when the

great treks began, and there’s lots of deep green forage down

here, while Spring grass is yet scarce up in Nebraska. The wagontrains

could actually fatten their teams on the first stages of the trail

from here. But the river bends, and the influx of both the Kansas

and the Blue Rivers at this point, mean you are always on the

other side of something, unsure which way is what. Missouri is

east AND south of the Missouri, while Kansas is west of it, but

north AND south of the Kansas. Got it?

The Owlers have gotten adept at finding their way to the heart

of the the big burgs, and scoping out the coming neighborhoods..

where the vegetarian restaurants are. We downramped just before

the skyscrapers and followed the scrubbed brick renos toward the

waterfront. Terry had told us to find Westport. The original outfitting

neighborhood. What we found was the City Market district, another

gentrifying quarter. Maybe everyone gets lost on the way to Westport.

There seem to be a host of coming sections of KC. A very decentralized

town. But lots of the centers are lovely. Including the City Market.

We shopped the veggie stalls and did caffeine and bakedgood under

a shade awning. Actually getting hot in the sun. I broke out the

colorbox and tried to fit the downtown skyline and the jumble

of stalls and storefronts into a single sketch, while Peggy cruised

the offerings. She reported that the crafts were a shoe-in for

the Machias Crafts Fair. That’s her low end of the esthetic index.

The cityscape was arty, though. The old brick warehouses are all

scrubbed, waiting for the new wave to break here. The vendor next

to me kept shouting: “We’re politically correct. We’ve got fruits

and nuts.” Subtle marketing.

So we hunted farther downriver (that’s east, right?). The downtown

has been so renewed by demolition and cut by cross-ramps that

we kept ending in cul de sacs, facing wonderful architectural

oddities, old and new. Splendid brick, sandstone, and plaster

elaborations. A stay-suspended sports center, freestanding over

an open roadway, supported by four massive pylons and A-line cables,

like a bridge over troubled pavements. A tower like Coit’s. A

heavily encrusted Baroque Contemporary hotel complex. Splendid

built diversity, scattered all over this sprawled metropolis.

KC Tower

Then we found the Nelson Atkins. Our Bowdoinham mentor, Carlo

Pittore, had promised this is among the best art collections in

the country, and it was our prime reason for coming here. Not

the prime rib. Another Greco-Roman mausoleum outside, but with

a vast sweeping lawn and sculpture garden luring us to explore,

on a glorious day. We park on the sidestreet, jump the stone wall,

step over the sunbathers, and amble onto the grounds.

Three 12-foot tall shuttlecocks have fallen on the long green, and a troupe of amateur dancers are stretching their choreographies on the great staircase. I say to the dancemaster:

“I hope you’ll all be waving badminton racquets.”

“Nice serve,” she says.

The Oldenburg shuttlecocks should have tipped me off, or the big

Calder mobile articulating merrily in a gentle wind. A museum

with this kind of lawn ornaments has to be of a different order,

Corinthian pillars notwithstanding. The Atkins might even cure

museumitis. A stupendous collection.

Oldenburgs

I homed in on the Thomas Hart Benton Hall, for openers. He’s a

native son who, like Grant Wood, chose provincialism over cosmopolitanism

after mastering the European idioms of the day. Benton struggled

with the question of AMERICAN art back in the 20s, long before

New York became the center of the universe. Dismissed as an ideologue

and a storyteller by the time I was learning about art, his powerful

style is still on civic surfaces all over this state, and elsewhere,

exhorting us to self-analysis. Here is the Grand Master of American

Realism, our version of what the Soviets were cramming down the

Russian gullet. It’s not to every taste.

One, Love

When I was digging out American travel journals last year, I discovered

Benton had gone on the road for a month or more every year during

the 20s. Usually with an acolyte, sketchbook in hand, he’d roam

the hinterlands trying to limn the character and characters of

the country. And written about it. The sketches found their way

into many of his well-known works, and seeing the evolution of

the images was fascinating. Now I could look at finished works

in the flesh. Gripping.

Benton’s manipulations of form, his torqued compositions, and

vertiginous angles make wonderful visual architecture. The perfect

style for a mural maker. His genius for turning a corner with

negative space is breath-taking. I hadn’t realized how much his

compositions owed to his native landscape. Missouri, like Wood’s

Iowa, is a quilted curvaceous patterning, and the way his spaces

all bend and mesh is like the integral view from his hills of

home.

There’s a paradox at the heart of Benton’s creativity, as is often

the case. In his books he describes the frustration of having

an esthetic vision as a youngster in Missouri. This is the Show

Me state, the kind of place where the buck stops, and he says

that the absolute utilitarianism of heartland America was a puzzle

for him. He was fascinated by THE THING IN ITSELF, not WHAT’S

IT GOOD FOR? He tells of losing a football game because he became

fixated on the shape of the ball instead of handing off. Typical

fuzzy-headed artist.

Benton's great uncle was the other Tom Benton, foremost Westerner

in Congress in the era of Manifest Destiny realized, creator of

California Fremont.. his son-in-law. Once our Tom could escape

his past, he plunged into the rarefied estheticism of the Parisian

revolution. Art for its own sake. It wasn’t until his mundane

assignments as an official illustrator during World War One (of

Baltimore shipyards, if I remember) that he began looking at the

American reality as a subject fit for art.

Black Robe & Indian

By the time he was embroiled in polemical debate with the art establishment over American Realism, he’d come full circle. He lambasted the effetism of an art whose subject was itself, and moved back to Missouri. He demanded an art which spoke to everyone, that opens our eyes to our local reality, our own essence. I don’t think this issue is dead yet.

An Oriental Pose

Benton was just an appetizer at the Atkins. Whoever selected this

collection wasn’t just counting coup on the big names. Every painting

and sculpture was memorable. Even artists whose work leaves me

cold were represented by pieces that made me doubletake. There

was actually a Matisse I liked (albeit an early portrait). After

I was neckdeep in American artists, I turned a corner into oriental

antiquities, and sank out of sight. By the time I stumbled out

of the India and China rooms, I was so eager to get my hands on

some wood that the local trees were in danger. My last gasp was

in the contemporary collection. It’s hilarious. What fun to be

in a big gallery with immense leg-pulls, seasoned with a dash

of more SERIOUS pieces, but not enough to spoil the taste. Those

shuttle-cocks out front WERE a clue.

Then I couldn’t find Peggy. Greek antiquities, usually a sure bet, weren’t being lovingly sketched. I wandered in circles, trying not to get captured by the art. Peggy was doing the same thing. She caught up as I was claiming my pack, and made me give it back to the guard. CARAVAGGIO, she gasped, and took me by the hand. Carlo has won another convert for Caravaggio and chiaroscuro. WOW.

St. John the Baptist

(After Caravaggio)

(Memo #103)

May 5 Thomas Hart Benton

Who? artist Thomas Hart Benton

What? drawings and paintings

When? twentieth century

Where? Nelson Atkins Museum, Kansas City & Missouri State House,

Jefferson City

How? commissions

Topics: regionalism, popular images in art, elitism and art

Questions: Why is Benton so attacked in the art world? What specific

techniques does he use?

Sketches after Benton

“I wanted to show that the people’s behavior, then the action

on the opening land, was the primary reality of American life.”

-Thomas Hart Benton

Thomas Hart Benton’s art enters our consciousness without any

active viewing - his images are simply everywhere. I THINK I saw

my first Benton on the cover of the paperback version of The Grapes

of Wrath I read in school, but who knows? His images are as much

a part of American popular culture as Coca Cola, Elvis, the golden

arches.

Few artists have the instant visual recognition that Benton does.

He is in the company of Georgia O’Keeffe, Grant Wood, Leonardo,

Michelangelo, Monet, Warhol, Dali. Huge poppies, fuzzy waterlilies,

melting clocks are icons, as are the sinuous curvilinear figures

of Benton’s mechanics and farmers. The instant recognition would

please him: Benton wanted to paint for the general public.

Washing Up

(Benton Mural)

This trip has provided revelations in American art. Grant Wood

and Thomas Hart Benton’s work has been belittled by the art establishment

as folksy, regionalist, sentimental, “illustration”. It is hard

to assess controversial and caricatured art (I have a fat file

of visual takeoffs on Wood’s American Gothic ranging from the

Clintons to Mickey and Minnie which make it hard to deal with

the original seriously). The galleries full of their work in Iowa,

Missouri, Oklahoma allowed us to reexamine them. How good is the

artist? How skilled are the techniques? How strong are the pictures?

Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton were realists in the age of

abstract expressionism, regionalist Midwesterners fighting New

York’s art snobbery. We’ve seen a range of their work (from still

life to portraiture) and are delighted by the skill and the vision

of the two men. Both were skilled craftsmen with a solid, classical

art training in Europe. Benton used egg tempera on the capital

murals after studying a Renaissance tract on the subject. Grant

Wood consciously created Renaissance portraits using Iowan subject

matter. They did not take refuge in visual platitudes, they consciously

chose rural themes. The in-depth museum commentary at Cedar Rapids,

Omaha, and Jefferson City shows their genius as technicians. They

knew what they were doing and were masters with paint and brush.

Thomas Hart Benton’s murals are as dramatic and tightly structured

as those in the Sistine Chapel. We saw Benton murals in two very

different settings. The Nelson Atkins museum in Kansas City has

a Benton Corridor with a number of small canvases and the incredible

American History Epic, two murals of five panels each. The ten

panels progress chronologically from prehistory to the industrial

age. There are stock figures - the missionary monk in habit, coonskin

capped frontiersman, tomahawk bearing native, the Conestoga wagon.

Each panel stands alone, in a frame, but there is a unity to the

ten. They are pulled together by the palette, the careful composition,

the style.

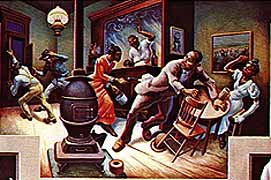

While Men Politic

The state capital in Jefferson City, Missouri, has a room with Benton murals on every bit of wall surface above the chair rail, even the space between the long windows. The subject is “A Social History of the State of Missouri.” The legislature appropriated $16,000 for the project, good pay for an artist in the 1930’s. It took Benton two years.

Thomas Hart Benton was an extremely methodical worker. He did

research, often reading extensively, before he painted. For example,

the early log cabin in the social history mural is a specific

French style used by the first Missouri settlers. The tools in

the mural and the working postures are accurate. For the Missouri

social history mural, he traveled the state for months seeing

the places and professions of the common people of Missouri -

the mural has miners and stockyard workers and farmers and seamstresses,

can-can dancers and mothers changing diapers. There is a great

deal of personal iconography. The two little boys fighting over

pieces of watermelon are the artist and his brother. The courtroom

scene was taken from his lawyer brother’s world. The politico

in one section wears the face of Kansas City Boss Tom Prendergast.

Benton is obviously a political artist, he did not choose the

glamourous and beautiful parts of Missouri. He showed beef being

slaughtered, industry spewing dark smoke. He uses the folk story

of the St. Louis murder of Johnny by Frankie. One of his most

monumental figures is a farmer washing up in a basin. His critics

said the subject matter was sordid and common. He even had a baby

being diapered (he sketched his own child!). He also has many

touches of humor, a woman looks into a neighbor’s basket, a spittoon

graces a corner.

Machine Pols

There was an uproar when the murals were finished and proposals

flew to whitewash the walls or paint out specific parts. Benton,

member of a politically renowned family, was clever enough to

figure that the legislators would leave his murals alone since

they had paid a lot for them!

Benton created preliminary sketches during his travels and then made three dimensional models in clay. In the state house model, Benton carefully included the room’s architectural elements - the doors and chair rail and windows. He extended the frames of the doors into the painting and carefully designed the planes in the pictures to move the action around the two major corners. He also tipped his clay models forty-five degrees to elongate the figures and use shadow more dramatically.

It is extremely difficult to stare fixedly at a Benton. Your eyes

move incessantly, in curves and along planes as Benton clearly

intended. If you begin to graph his work, you recognize the intricate

planning, the patterns that repeat, the flow of negative space,

the crisscrossing diagonals. The line of a gun will be echoed

in a fence on the other side of the picture, the curve of a back

will be echoed in an adjacent figure’s upswept arm. There is symmetry

on either side of the central doorway, columns of smoke lift to

both skies, the plowing donkey on one side is balanced by the

cow being milked on the other.

Frankie & Johnnie

Benton’s murals are visual collages, many different scenes are

welded together and the juxtaposition is fascinating. A courtroom

juts into a farmhouse, an abattoir fades into a laboratory. He

will use a prop like a split rail fence to link parts. One wall

is neatly ended about four feet up. The shifting perspective and

intersecting planes are reminiscent of Escher. The contortions

and elongations of his human figures suggest Rodin. Benton had

the chance to study European art during his years in Paris. Benton

also used popular media, consciously adapting cartoon elements.

There are Benton murals in the east, in Connecticut and New York

which, we hope to see. He is an amazing artist.

5/4.. cont.

Peggy after Rodin

Brimful we bellied out of the Atkins into the springshine, to discover it was late afternoon.

Too late for the Truman House and Library (with their big Benton

murals). Too late for the World War One Museum. The KC Art Institute

won’t be open til Tuesday aft. We’d given our all to the Atkins.

We went back into Westport for a Middle-Eastern repast, catty-corner

to Kelly’s. Where the emigrants bought their trail goods. We might

have gone in for a stirrup cup, but the sign said. PRIVATE PARTY.

Saddle-up. Eastward Ho.

Peggy plotted us through the outer burbs, much more conventional

here. Brobdignadian bungalows on Lilliputian lots. Then we were

on a two-lane with the sun casting Owl’s shadow far ahead of us.

More of the comforting rise and dip. Standing waves.. from a big

storm way off shore.. lifting up over shoal ground. But I’m a

steady rolling man.

Missouri is totally new to us, and completely familiar. I could

happily sink into this landscape. Even the cattle smell good.

Grant Wood quiltworks. Hulking hardwoods, greening out. The curvaceous

contours. If I had to pick a single idealized American scene,

the embodiment of a settler’s dream, I’d chose the hillcountry

between the Missouri and the Ozarks. It feels rich and looks cozy.

Have I been groking too much Benton on a spring day?

After Benjamin West

Peggy had aimed us at Jefferson City, the capitol. When we got

there it was sunset, so we checked into a roadflop and went down

to the river, to watch the mud flow, and check out the bridges.

A strange pair of trussed arches, leaping from shore to shore,

with the roadways bending between the gridwork. As though a giant

had squashed two hemispheric arcs flat, and taken all the grandeur

out of the design. The capitol is another bit of Byzantine state

monumentalism. Then, I got all excited. I remembered there are

Benton murals somewhere under that proud dome.

We got lost trying to find our way back to the motel, but were

too slap-happy to bark at each other. And I finally got through

to an old classmate (we are all getting to be old classmates..

now) in St. Louis. Peter Schandorff. We make a date for tomorrow

afternoon. And put it to bed smiling.

5/5.. Jefferson City.

Morning in the Missouri Halls of Power. Echoing marble corridors. Soaring interior heights. Three-piece

suits and noncommittal stares. And dandy memorial art. Splendid

busts of Great Missourians under the rotunda. From Harry Truman

to Josephine Baker. Emmett Kelly and Sam Clemens. Omar Bradley

and the Bird who flew too high: Charlie Parker.

I’d expected the Benton murals to be in a prominent place, the

rotunda perhaps. But even on his home turf Tom was a controversial

guy. We were directed to a closed room at the far end of the third

floor. “Just step on the threshold,” we’d been instructed. It’s

an hydraulic gizmo. Your weight opens the double sliding doors.

Ain’t America a gas?

POW. A room maybe 20X60 with 15 foot walls FULL of images from

Missouri’s history. And Benton doesn’t slough a card. Slavery

and betrayal. Slaughterhouses and shoe-factories. Diapering the

baby and machine politics. Frankie and Johnnie. Boss Prendergast

presides over a political confab in one corner of the room, with

Harry himself in the front row. We tend to forget that Truman

was a machine pol who rose above self-interest and graft. Apparently

some of the state officials were shocked at Benton’s treatment

of their history and called for a whitewash. How Benton must have

chuckled. Assign him the task of illuminating a smoke-filled room..

this is the representatives’ caucus room.. and then object to

the down and dirty? He must have loved it. His family had been

hustings hustlers for generations, now he could leave his mark

on these walls.

Artists

The more you look, the more there is to see. The balance of figures

and forms to turn your eyes from plane to plane. The tongue-in-cheek

commentary of symmetrical images. Every figure in the the composition

has its counterweight visually, and conceptually. Indians and

settlers matched to beef and hogs to the slaughter. Racial field

slavery to factory wage slavery. Corn stalks to power pylons.

Breath-taking. Peggy whispers, “It’s an American Sistine Chapel.”

My favorite vignette is a backdrop detail behind the Prendergast

party in the Kansas City montage. There’s a cartoon of the Atkins

Museum, with three derelicts warming themselves by a trashcan

fire out front. Wonder which three artists Tom caricatured. Sly

old fox.