American Sabbatical 023: 9/28/96

South Pass

9/28.. continued

So now where? We were almost to the east gate of Yellowstone Park, but the

road was reportedly closed by icy conditions.. and we wanted to

cross the continental divide on the emigrant trail, which is to

the south. Peggy insisted that we backtrack to join the Oregon

Trail at the North Platte and follow the Sweetwater over South

Pass, knowing that was one of my fancies. And it just happens

that THE WORLD'S LARGEST MINERAL HOT SPRING is between here and

there. In Themopolis.

| Those of you who know that Peggy has lived without a plumbed bathtub

for the last 12 years, without making a loud plaint.. that she

has accepted the spacial utility of hot showers vs. the therapy

of the bath with only an occasional soft groan.. they can perhaps

imagine her glee today as we rolled through a dramatic Westscape

into Thermopolis. |

Hot Mineral Springs

|

But can you find the hot spring for the spa? Do you have to ride

the waterslides? Buy taffy and trinkets? As we drove between the

Inns-with-massage, past manicured lawns with tropical umbrellas,

we wondered how much this whim would set us back. We under-estimated

the state of Wyoming. The State Bath-House is FREE. So, among

the sulfurous reeks and steams, under a cloudless sky, we washed

it all away.

Emigrant Train

(Alfred Jacob Miller)

|

Struck up conversation with a couple at the waters.. actually

in the waters.. he runs wagontrain reenactments for dudes and

filmmakers, and was soaking away the bruises from muleskinning.

After a bit of prodding he began to wax poetic about taking flatlanders

onto a higher plain. He said that the West represents the American

Dream. The quest for individual fulfillment in a new world. He

tries to connect his clients with a Native sense of the land as

they recreate the emigrant experience. Here we were in up to our

necks again with the two cultural currents flowing together. Newcomers

seeking Nativity. Catlin goes to Hollywood. |

We moved slowly out of the fumes and plunged into the Wind River

gorge. Up stream into a deep cleft through Precambrian granite

and 500 million years of overburden. Thought we’d just sloughed

that off. The sparkling river swirling over gavel bars was full

of fly-fishermen (and women) making their glistening ritual with

wands. Then we climbed up to the Boysen dam and reservoir, and

the panorama of a drowned tableland with the Wind River Range

on the horizon beyond. Another hundred feet up and we were back

on the big empty, with another 100 miles of it to Casper. Just

jackrabbits, antelope, tilting oil rigs, the bronze grasses and

the dusty sage.

Wind River Gorge (Bryce)

We had hoped to get a sense of the last prairie miles of the emigrant

trains before they rose the shining mountains up out of the plains,

but we’d forgotten that would mean backtracking ourselves. It’s

ok to wax slickly about the sweeping smooths first time around,

but we’ve been up the hill now, and.. And Casper is a different

breed of Wyoming. At least coming in from Thermopolis. The suburbs

are all oil rig supply dumps and rigger bars. The sunset was jabbing

us in the eyes, the traffic was Saturday night rude, and downtown

Casper could have been any cement metropolis. We were back on

the main street of America, to be sure. Anywhereville with MacBurgers.

So we slumped into a Super8 on the banks of the Platte, feeling

like we’d been muleskinning all day. Out of the picturesque and

back on the History Trail.

9/29.. Over the top.

| While Peggy put together her school messages in the early AM, I went for a walk along the banks of the North

Platte River, looking for the footprints of the emigrants. The

Oregon trail ran right below the Super8. Very convenient. We had

made a long day’s swing east and south to pick up the trail, and

I was sniffing for old traces. All I met was a quintet of labs

on their morning run, along with their people, and I got muddy-pawed

and otherwise caressed, as I deserved for playing hound. |

Along the Platte

|

It’s a long slow poke over the Great American Desert, even in

a Festiva at 65. That is, when she’ll do 65. We were slam-to a

hard westerly, hot and dusty. The air had that dessicated texture,

and the scene had that washed out coloring that says West to me.

And Festiva was laboring hard against the hot buffets, while our

local star was searing any exposed flesh. This historical verisimilitude

can go too far.

Independence Rock

(Miller)

|

The deadly flatlands began to acquire edges as what looked to

be molten rockpiles rose up alongside the plains. Ahead of us

was one solitary glob which looked especially fresh-laid. As we

flashed by the sign say “Independence Rock.” Hard U-ey, Festivites.

There it was, America’s monument to graffiti. The place where

those crossing over to a new life would stop and scratch their

Jim Bridger on the gray granite. If you got there by July 4, you

would probably get to Oregon before the passes closed, another

reason to celebrate the Fabulous Fourth: hence Independence Rock.

|

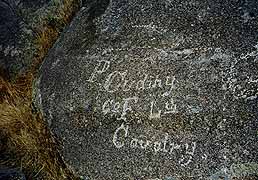

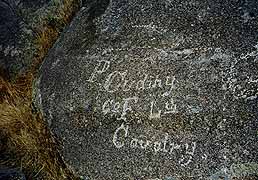

Jim Clyman in his journal of 1844 remarks that he found where

he and Sublette and Fitzpatrick had left their marks in 1824.

We couldn’t find them. But it is amusing to see the wall of this

great glob of rock fenced off so nobody can deface old graffiti.

Who says wickedgood is something new? We joined the historic spirit,

had our nooner by the rock, and traced some old scratchings with

our fingers. Then we used the state of Wyoming’s sparkling roadside

facilities. Something the wagoneers might have liked. When we

commented to a Wyomingite about this courtesy to travelers, and

how you couldn’t find public restrooms in Maine, she observed

that it was probably because the sagebrush is so low.

| It's uphill all the way from where the Platte joins the Sweetwater,

the ultimate tributary of the Mississippi system on the emigrant

trail, and Festiva was dragging her tired feet. We stopped at

every historic pullover (and Wyoming has more pullovers than L.L.

Bean). Devil’s Gap, Split Rock, Gasp For Breath, and Woah-up.

Finally I remembered a mechanic’s advice from Bowdoinham. I disconnected

our pony’s battery, and recycled her brain. Just like a bag of

oats for a tired pony: with new computer settings she fired up

her octanes and charged uphill like.. well like a Festiva with

105,000 miles. Yup. That’s right, we’ve put 6K on the darling,

and we’re only half way up the Oregon Trail. Be kind to the horses. |

Devil's Gap

(Miller)

|

The Sweetwater is just a little sister to the Platte, and she

shrinks into a backyard brook as you climb to 7000 feet. The vegetation

in the valleys we were following changed from cottonwood bottomland

to high plains gully to alpine meadow-and-swamp as we approached

the top of America. There were beaver houses and ponds punctuating

the tumbling stream, aspen and firs tucked into the hillsides.

We’d made an immense long climb to the heights of the continent.

Now we were looking in all directions for signs of the storied

South Pass. The slot that hundreds of thousands of starry-eyed

travelers had passed through on their way to tomorrow. But the

sun still seared, and the long slopes wouldn’t quit.

High Waters

|

When we came to a sign for Atlantic City and South Pass City,

we swung off onto the dirt road, expecting another historic outlook.

But, seven miles along the gradings, we came down a wiggle in

the hills into a company town. The Atlantic City Mine perched

on its hill, and the employees were clustered together in log

cabins, trailers, and small frame houses, all higgle-piggle up

a gully, looking for all the world like a 19th Century mining

town. Log chapel with rickety frame bell tower, the works. |

Then two miles farther and you are in South Pass City, a reconstructed

19th Century mining village (without all the junk in the yards).

This gem was totally unmarked in the guides we’ve been using,

in fact it is a new addition to Wyoming’s tourist bait collection.

Just the bare bones of a town, in a bare bones place. But the

feeling of time and place are strong enough to make your head

spin, or maybe it’s the altitude. We did the ritual walkabout.

| Half a mile father west are the graves of two women travelers

who never made it over the watershed (one was the Oregon missionary,

Whitman’s, first wife). We didn’t pause to commiserate. The top

of the hill had to be in sight. And then it was. A great wide

saddle easing over America. The snow-capped Wind River Range standing

to the North (hence South Pass), and the Antelope Hills to the

south. At the sign “Continental Divide” we yelled “YEEHAW, California

here we come!” |

South Pass City

|

Now the sun was squarely in our eyes and we were a couple of beat

emigrants looking for a waterhole. But the downslope is just as

empty and endless as the up. The towns out here are few and unmotelled.

The next likely crossroads was 130 miles away. We started to sag

a little. But Seth’s FREE CAMPING book came to the rescue. There,

just 8 miles down a dirt road, was Big Sandy Campground. Big as

in wide open, Sandy as in bare as.. well, bare. But there were

sundown flaming mountains east and west, and we off-loaded Festiva

alongside one of the uppermost tributaries of the Colorado River

(via the Green). Over the hill and far away.

Camping at Big Sandy

|

A couple of hunters from California came around the waterhole

(a reclamation lake) to wash their hands after getting their antelope,

and stopped to brag a little. They said the locals thought them

nuts to drive from California to kill “goats”. I asked if the

early travelers’ reports were true, that antelopes were difficult

to approach, and did they use the old trick of lying on their

back and kicking their feet in the air to lure them in. They laughed,

and said they were hard to get close to, and they did wave a handkerchief

at them to turn them for the kill, but hadn’t tried waving their

feet. Then everything turned purple, and yellow, and green, and

black. The stars came out and we all fell down. |

Yup. After that scorching day it FROZE in the Big Sandy valley,

and we wondered again about our sanity. BUT: so far we have camped

1/3 the time, visited with friends 1/3 the time, and only motelled

1/3 the time.. so we might be able to afford this craziness. In

the night a spookbird visited our encampment and cried his eeriness

into the old moonlight. When I went out, our gibbous neighbor

was whitening the mountains, and the frozen air hung shining over

the sagebrush. I cold-footed it back into the tent.

Sunset at Big Sandy

(Memo #23)

Sept .29/30 - Oregon Trail and South Pass, Wyoming

Who? trailblazers James Bridger and Thomas Fitzpatrick

What? Oregon Trail from Independence, Missouri to Wilamette Valley,

Oregon

Where? up Platte River to Sweetwater River, over South Pass

When? most heavily used 1843-60

How? wagon trains

|

Oregon Trail

|

|

Topics: Oregon Trail, westward movement, US geography, Great American

Desert, South Pass, Independence Rock, emigrants.

Questions: What was it like on the Oregon Trail? How are the High

Plains different from the Low Plains? |

|

All the way west, we’ve tried to stay off major highways. There

is one” major highway” we’ve wanted to use - the Oregon Trail.

We drove to Casper, Wyoming, on the Northern Platte River and

followed the Oregon trail west through South Pass over the Continental

Divide.

Along the Platte

|

The estimates are that 350,000-500,000 people traveled west over

this route mainly in the 1840’s and 1850’s. It was the main overland

route to the west coast before the railroads. Travelers started

from settlements in Missouri, they had to be through the mountain

passes of the Rockies by fall. They traveled in Conestogas wagons

pulled by teams of oxen or horses, hauling all their worldly goods.

We have all our goods for the trip west in the back of a small

car, but we’re not trying to homestead at the end. Over 2000 miles

at ox pace.

|

Why Oregon is a key question? It was a misperception of the geography.

The Plains were seen as useless for farming since only grass and

shrubs grew there. The early settlers called the land between

Mississippi and mountains the Great American Desert. Settlers

were used to eastern woodlands, felling trees to clear fields.

When I saw Iowa I wondered how any settler could pass its beautiful

grassy river valleys by. It seemed ideal farmland; not so central

Wyoming.

High Plains

This is why it’s useful to distinguish the HIGH plains from the

LOW plains. The low plains mean low in elevation and they are

also called the highgrass prairies or the eastern plains. These

really are much “lusher",with rolling grasslands that look like

what we would call “fields” or “pasture”, the grass is thick.

There are many rivers and springs and TREES along the water courses.

Early reports say the original grass in the eastern Plains could

hide a man on horseback! The high plains of central Wyoming, Montana,

the Dakotas ARE desert even though animals survive on the sparse

vegetation.

| Central Wyoming really looks like a desert. The main vegetation

is sagebrush in regular scattered clumps (at most waisthigh bushes).

Some grass patches and tiny plants, but most of the land is barren

ground, dirt and rock, with few trees. We camped in a unusual

“grove” of four trees. The hills are stark. The beauty of the

land is the colors of the rocks and soils - browns and beiges

and pinks. We were constantly aware of water and began buying

a gallon a day for drinking. The wagon train travelers had to

use the river water and springs. In this part of the west the

waters are often mineral laden, foul to the smell and taste. The

tourist literature always tells you to be careful of water. You

shouldn’t even drink from a high mountain steam. |

High Desert

|

The trip is hard even in a modern car. In late September it was

HOT during the day, very cold at night, windy. My eyes dried and

my lips got chapped from the heat and wind. I used dark glasses

and a hat and first aid cream; what did the early travelers use?

The air shimmered from heat and a single truck on a dirt road

left a long plume of dust. Distances dragged. I found myself imagining

the heat and dust and smells and noise of a line of wagons. Wheels

creaking, cattle bawling, people yelling. Slow travel - ten miles

a day, seven miles a day. And always the threat of attack by Indians.

Sweetwater

|

We drove across the high dry desert of central Wyoming up the

North Platte River to its tributary, the Sweetwater River, still

driving west following the Oregon Trail. The Sweetwater is small,

perhaps thirty feet across, slowmoving with many oxbows. |

| Independence Rock is a huge rounded gray stone hill that sits

by itself. You see it from miles away. The wagon trains would

camp at its base. Wagon train members carved their names on the

rock near its base. You can still read inscriptions and dates

...1842, 1846..... One was “J. Wheelock and wife”. There was also

a small graveyard. Like the early travelers, we walked around

the base and climbed a way up to see the view. It must have been

a break in the monotony of the long trip to rest in the shade

and climb up. I imagine myself in 1845 walking with a friend,

gathering up our full skirts and giggling as we clamber a way

up. There seem to be voices on the wind. |

Independence Rock

|

Old Graffiti

|

Excerpts from diaries are on the information building’s walls.

A two-year-old girl was left behind one morning, another wagon

train found her and brought her on! In ways its was lonely travel,

but there were many wagon trains moving out at the same time,

sometimes on parallel courses, sometimes a few miles behind one

another. |

|

The travelers were called EMIGRANTS on the Emigrant Trail, a reminder

that they were leaving the United States for unsettled territories.

There are constant road markers for modern travelers to show you

the trail and its landmarks: Split rock, Devil’s Gap. We then

began the climb to South Pass, the key to conquering the Rockies.

The highway takes incredible upward swings somewhat to the north

of the trail, up through steep ravines with pines and yellow aspens.

South Pass is a wide flat stark brown plain at the top of America,

swept by cold winds. There are distant mountains to the north

and south. We saw patches of snow. Did the early travelers feel

the same thrill at being at the top of America? |

Travelers at

Independence

Rock

|

A beaver dam in a ravine reminded us that the first white men

to live in the Rockies were the French coureur de bois and the

Mountain Men hunting for furs for Europeans and easterners. The

first white economic enterprise in the Rockies was fur trapping.

At first the trappers made yearly forays into the mountains, then

the fur companies began sending out the supplies so the trappers

could stay year-round in the mountains. They would trap in fall

and spring when the pelts were good and then haul the hides to

the annual summer rendezvous site in the mountains for trading

and socializing. The rendezvous sites are well marked throughout

Wyoming.

High and Dry

|

We also saw evidence of another Rockies economic enterprise: mining.

A side road took us to two wonderful settlements - Atlantic City,

an isolated ravine village of small cabins and houses which still

has a mine, and South Pass City, an outdoor museum. |

South Pass City was first a telegraph and stage stop for the trail

in the 1850’s and flourished during the gold days of the late

1860’s when its Carissa mine was producing and it was home to

2000 people. It had seven hotels, saloons, newspapers, a Masonic

lodge, even a pest house for isolating the ill. It is a ghost

town today. 33 buildings remain along the long main street, offices

and houses and hotels are largely furnished with original objects.

It seems as if the people have just stepped out.

Wind River Gorge (Peggy)