American Sabbatical 86: 4/5/97

Civil Rights

4/5.. Monroeville.

Breakfast at Joe and Pat’s again featured fresh baking, and we decided we’d better escape

quickly, before we begged to be adopted. We put on our feathers

and started to beat wings out of Fairhope. But which way?

The thought of more flatlands, or holiday crowds, made arriving

in New Orleans this week less tantalizing than it had been. Hills

and backroads beckoned sweetly. Peggy wanted to visit Monroeville,

Alabama, where Harper Lee wrote To Kill A Mockingbird. It’s about

an hour’s drive northeast of Mobile. Maybe it was time to zig.

A hard southerly was thrashing the trees, so we turned our backs

to it and blew upcountry.

We stopped on the way to visit Momma Dot at a hospital in Daphne,

just up the Mobile Bay shore. She was eager to talk to Peggy,

but was scheduled for therapy, so we unbagged our laundry at a

local suds-and-spin, and endured the ennui of watching fabrics

tumble. Then Peggy and Dot traded teacher-talk for a couple of

hours.

By the time we cleared Mobile Bay the ceiling was brushing our

hairdos, walls of turbulent black clouds were moving in on us,

and scattered drops splattered Owl’s face. We sidestepped onto

the sideroads, and the country, even in this ominous light, was

beautiful. Nobody warned us that Alabama can seduce you with her

passionate vegetation, and the roll of her hills. And armadillos?

Had we been advised about armadillos?

I’d imagined sharecroppers shacks, worn out cotton land, holloweyed

crackers, and mean dogs. Instead we get rippling green pastures,

dense stands of tall hardwoods, ridgetop vistas of receding treelines,

and tidy houses hunkered in shady groves. There’s rural poverty,

to be sure, shotgun houses teetering on blocks, with matching

parts cars, and abandoned looking tin boxes, mobile or traditional,

with dooryards awash in litter. But they are infrequent. Most

of the old houses are maintained with pride: the modest hiproofed

single-story-with-porch, as well as the antibellum-style manses,

pillars and pediments and all. And undemonstrative churches everywhere.

Gas stop in the crossroads town of Uriah. Old molded cement-block

post office and general store, with silver-white metal roofs and

porch awnings reaching down low to let the rain sluice wide. The

very image of the old rural South. And the sky opens up.

Spring rain in Dixie. Coming straight down in torrents. We limp

along, wipers slapping, working the defrost to cut the steam,

then the blowers to dry the sweat. Eating oranges and peering

at the roadsigns. The yellow-orange clay looks rich and oozy.

The ditches run like blood.

Downpour. Then the blackness lifts and it’s just raining. Then

downpour again. By the time we make Monroeville, the Courthouse

Museum is closed, the town is shut up, the water is standing deep

everywhere, and our slopping around in the puddles only gets our

feet wet. We quarter the downtown blocks looking for scenes out

of the book, visit the elementary school, and finally abandon

the quest for a dry room and a warm phonejack.

(Memo #76)

April 5 Harper Lee Monroeville

Who? author of To Kill a Mockingbird

What? author’s hometown used as model for book’s setting

Where? in south central Alabama

When? Pulitzer Prize winning book set in 1930’s, written in 1960’s

How? Harper Lee drew on her own life and hometown

Topics: Southern literature, setting, fame and tourism

Questions: How accurately has Harper Lee portrayed her home town?

Does the town of Monroeville capitalize on her book?

|

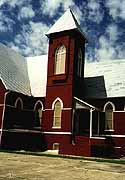

County Courthouse

|

I don’t know what I expected at Monroeville, Alabama, perhaps

another Hannibal, Missouri. Mark Twain’s hometown has so hyped

his books and characters that there are signs on Hannibal street

corners explaining what Huck and Tom did nearby. The whole town

seems to be involved in a conspiracy to convince visitors that

the events and characters in Twain’s books were all real. Would

there be Scout and Jem statues in the courthouse square in Monroeville?

Would Harper Lee’s house and settings be identified on cutesy

tourist maps? Would children’s overalls be described as being

“like Scout’s”? How does a Pulitzer Prize winning book affect

a small town in Alabama? Harper Lee’s characters and setting are

so vivid and real to me (even after thirty years) that I expected

to have a constant shock of recognition in her hometown.

I did research on Harper (“Nelle”) Lee before we set out on this

trip. Related somehow to Robert E. Lee, she was born and raised

in Monroeville where her father Amasa Lee (the model for Atticus

Finch) was a lawyer. “My father is one of the few men I’ve known

who has genuine humility, and it lends him a natural humility.

He has absolutely no ego drive, and so he is one of the most beloved

men in this part of the state.” She and her sister both studied

law at the University of Alabama. Ms. Lee moved to New York City

and worked for an airline while writing Mockingbird. One wonderful

article photographed her in her hometown - in the balcony of the

courthouse where she watched her father argue cases (like Scout)

, at the Old Hodge place (a haunted house that may have been the

model for the Radley home), in the schoolyard. “The trial (in

the book) was a composite of all trials in the world - some in

the South. But the courthouse was this one. My father’s a lawyer,

so I grew up in this room, and mostly I watched him from here.”

The quirky boy who comes to visit his Aunt for the summer was

apparently the young Truman Capote. My research turned up no information

about any other books she wrote after Mockingbird or what she

did after the 1960’s. Still, it was enough to make me go to Monroeville.

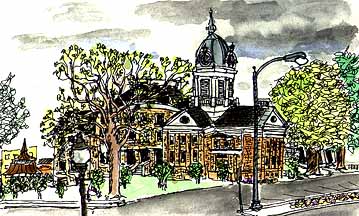

We drove north to Monroeville through rolling green farmland and

forests. A modern strip mall lead us toward town. As we entered

the town center, we saw the old elementary school (was that the

schoolyard where Scout and Jem were stalked?). We pulled into

courthouse square in Monroeville just after 2 pm on a Saturday.

There were few cars on the streets and many of the buildings that

edge the square were empty. It was pouring rain. The museum was

closed. The red brick courthouse in the center of the square was

closed, but there was a sign identifying it as the setting in

Ms. Lee’s book. A sign on the museum said you could buy tickets

to the play of “To Kill A Mockingbird”. There was no other information

(time? date?) available.

We drove back and forth around town looking for....tour signs

or a bookstore featuring her book or a Mockingbird Cafe. Nothing.

I began looking for old houses, haunted houses, a picturesque

jail (like the one where Atticus sat to protect Tom). The Monroeville

police station is right by the square but it is a large, modern,

brick building

(no barred windows visible). The houses are mostly low 1930’s

bungalows with deep porches. It is a quiet unremarkable town.

The town square does have a Katherine Lee Rose garden with no

explanation. I took a few pictures. Frustrating.

When we checked into our motel, I asked the receptionist if the

town did much to note Harper Lee’s success. “Not really,” she

said. “We kind of just grow up with it.” She knew nothing more

about Ms. Lee. There were no tourist brochures in the motel lobby.

No tram tours. No posters. No Harper Lee memorabilia. No mugs.

There was a single historic postcard of the courthouse. Maybe

living authors are allowed some anonymity.

Frustrated again, I decided to try the phone book. I called the

museum and a tape told me tickets were still on sale but the third

was sold out (it was the fifth!). There was no “H.Lee”, no “Mockingbird”.

Hmm.. an “F.Lee” is practicing law (her sister?).

I guess it’s rather nice that Monroeville has resisted becoming

another Hannibal. There is an argument to be made that the magic

is in the book, not in the author or the hometown. Maybe it’s

enough to read “To Kill a Mockingbird”.

4/6.. Selma and Montgomery.

Sunday morning and the whole state is at church. There are still some marching

lines of cumulonimbus shadowing the sun, but the air feels dryer.

Going to be a fine day.

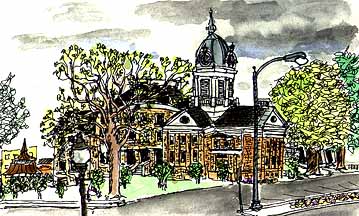

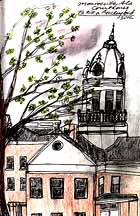

Monroeville Courthouse

The Monroe County Courthouse demands that we stop one more time,

and take her measure with ink and colors. A classic courthouse

square, with commercial blocks on the four sides, across wide

streets. The ornate clocktowered brick courthouse set among stately

live oaks and careful flowerbeds.

Our Sunday journey SHOULD begin at this storied courthouse. We

are going to follow traces of the Civil Rights Movement, and that

battle was fought in the courts as well as in the streets. In

this day when it’s easy to be cynical about special interest law

for those who can afford it, we may forget that a long struggle

for racial equality under the law began in petty courts like this,

and culminated in such decisions as Brown vs. Board of Education.

Harper Lee’s fictionalization of her father’s practice continues

to remind us that justice may be found in a courtroom, and that

Bull Connors isn’t the only Southern white archetype.

The Owl swoops toward Selma. The backroads seem very familiar

here. It could be Maine in July. The mix of pine and hardwoods,

new cars and beaters, gentle ridge and valley, good forest practice

and bad. We have the roads mostly to ourselves, and flush a pair

of turkeys somewhere near Beatrice. There are foothigh mounds

of dirt along the shoulders, like the works of giant prairie dogs,

but no residents in sight, unless the occasional roadkill armadillo

is a clue. The floral speciation is totally different, of course,

with many more compound leaves, and almost fernlike patterning,

longleaf pines vs. the whites of home.

Instead of the sagging clapboard capes of backroad Maine there

are rusty galvanized cabins with low eaves and deep porches, swallowed

in kudzu. Folks are gathered in the churchyards. One a desperate

old tin structure with a crooked steeple, and the cars lined up

under the trees in the dirt yard. But everyone in their Sunday

best, and most of the churches are as foursquare and tended as

any in New England.

There IS something shabbier about rural poverty in the South,

when you encounter it. It may be because the weather lets you

live in a place more exposed, or it may be the building materials.

A Maine house let go may lose its paint and look rustic, but galvanized

siding or cinderblock just gets rusty and dingy. There isn’t our

love of wickedgood paint out here in the kudzu.

Suddenly we’re driving over the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and back

into history. This is where Civil Rights marchers behind Martin

Luther King Jr. were stopped, and America was confronted, thanks

to a watching media. Another institution it’s easy to denigrate

now, but where would Dr. King and the others have been without

the press? How many of us remember that a French journalist was

killed at Ol’ Miss during the integration riots?

Edmund Pettus Bridge

This Sunday Selma is a ghost town. Wonderful ornate storefronts

empty and boarded up. Any downtown in New England as charming

as this would have a health food store, a bookstore, and a gang

of local artists. A place ripe for resurrection, but dozing in

the sun. A few fishermen idly twitching lures in the Alabama.

The low buzz of through traffic.

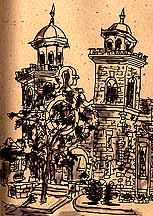

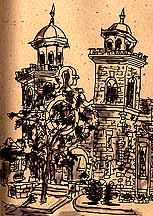

| We follow out Broad Street to the Visitor’s Center, and Peggy

gets a lecture on Disney Love Pops (“Americas best selling candy”),

and the other contemporary claims to fame. As well as a walking

tour guide and a map. There’s a four-block tour of voting rights

history, and Peggy makes the ritual moves, while I sketch the

AME Chapel in the third block, a twin-turetted brick bit of pride,

trimmed in white. |

Fishin'

|

Brown Chapel

|

Across the street is a housing project. Long single-story brick

multiples. The streets and yards are full of kids and young men

making converse is the hot sun. One comes over to check out my

drawing. Tells me a halting tale of “a friend” who writes poems

“from the heart... Has a whole book full.” But can never get them

published. Can I make money with these drawings? I tell him probably

not. That isn’t what they’re for. That the doing is the thing.

That they’ll bring me back to this place, and this talk with him.

To tell his friend to keep the faith, and read his poems to everyone

who’ll listen. That’s what they’re for. |

“You a man with a vision,” he said.

This community had a vision 40 years ago. And it was in the church

congregations that those visions were organized. Selma has a wonderful

collection of brick-steepled churches, and is proud of more that

their architecture. Here again we tend to equate Southern churches

with reactionary politics and hidebound prejudices. We forget

that Dr. King was a preacher, and it was the churches of Selma,

black AND white, that mobilized for equal justice.

Do you remember the excitement? As a high school kid I was intoxicated

with the thought of a people rising up in a noble cause. Do you

remember noble causes?

Peggy strode out across the Edmund Pettus while I tried to make

a quick rendering. It was a revolutionary structure in its day,

a steel arch like the Hell Gate RR Bridge, approached by two leaping

cement arches. Another synapse where an idea crossed over, paradigms

shifted.

| We recrossed Edmund and followed the march route to Montgomery,

heart of the heart of Dixie. If you’ve gotta walk a highway, this

is a good’un. Running the ridgelines across rolling woodland and

pastures, it feels like the Taconic State in the Hudson Valley,

at least until you dump out into the paved exurb of the state

capitol. |

Pecans

|

The capitol city itself is shut down for the day, and scrubbed

down forever. They must have renewed the hell out of Montgomery.

It is as sterile a monument to bureaucracy as I’ve ever seen.

That ol’ George Wallace was something else. Every building is

lily-white. Except for the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Martin’s

church, just a few steps away from the capitol. This modest brick

antiquity must have been a thorn in the side of entrenched segregationist

power. Caddycorner to the Dept. of Justice, smack in front of

the rotunda stairs.

The Civil Rights Memorial is just around the corner, and you have

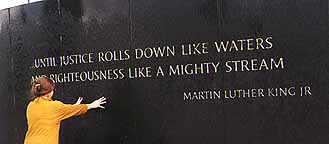

to credit the New South for honoring all of its past. Here in

the first capitol of the Confederacy, the big tourist attraction

is a black marble wall with flowing waters over a quote from Dr.King.

“..until justice comes flowing down like waters...”, and a black

sundial fountain memorializing the events and martyrs from Brown

v. Board to a day in Memphis. (And yesterday Coretta King met

with James Earl Ray and said she thinks he is innocent.) An all-white

gaggle of kids from Atlanta wearing T-s proclaiming “Faith Shout

Chorus” were playing around the waters, while an armed white security

guard watched, and their female black busdriver sat in the front

of the bus, smiling.

Homicide Protest

|

Political protest isn’t dead in Montgomery. The Justice department

lawn was covered with threefoot tall white crosses. Alabama homicide

victims in 1996. |

(Memo #79)

April 6 Selma & Montgomery

Who? Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, SNCC and SCLC leaders

What? cities at center of Civil Rights movement

Where? in central Alabama

When? 1950’s and 1960’s

How? a long series of events made them the focus of the civil

rights movement

Topics: Civil Rights Movement, Voting Rights Movement, integration,

protest marches, bus boycott

Questions: Why Selma? Why Montgomery? |

Montgomery

|

Selma and Montgomery, Alabama, are much more than places on a

map. They are icons of the civil rights movement, places memorialized

for the courage and dignity of marchers and protesters and boycotters.

Montgomery is identified with the bus boycott sparked by Rosa

Parks, and the state government lead by George and Lurleen Wallace.

Selma is identified with the voting rights movement and the march

on the capital. Many heroes of the Civil Rights Movement were

active in this part of Alabama: Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis,

Hosea Williams, Stokeley Carmichael. SNCC, the SCLC. Some people

were killed during the Selma protests: James Reeb, Viola Liuzzo,

Jimmy Lee Jackson. Anyone over fifty will remember the stunning

pictures: the boycotters walking miles to work in Montgomery,

the line of marchers turned back at the Selma Bridge.

The more you delve into history, the more complex things appear.

You can’t start the Selma story in 1965 when the marches occurred

nor can you date Montgomery’s protests to the arrival of young

Martin Luther King. Blacks and whites had been actively promoting

civil rights in both cities since the Civil War and the passage

of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. For a brief time after

the Civil War blacks had many rights, these were destroyed by

the Jim Crow segregation system that arose in the late nineteenth

century. Protest has been continuous, from W.E.B. Du Bois and

the Niagara Movement through the establishment of the NAACP (1910),

the Urban League (1911) and CORE. CORE held sit-ins in Chicago

restaurants and skating rinks in the 1940’s! In the 1950’s and

1960’s the new leaders were in the SCLC, SNCC, the Black Panthers.

The movement heated up with the Supreme Court decision (Brown

V. Board of Education) in 1954 which outlawed segregation in education.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-56) was a test of segregation

in transportation; the Selma marches (1963) were a test of limited

voting rights. Chronologically, Montgomery came first, but we

started in Selma.

Over Troubled Water

|

We drove into Selma over the famous Edmund Pettus bridge. Downtown

is right on the other side with many empty lots and closed stores

with wrought iron trim and long verandas. The town center has

a number of beautiful stone churches, wide avenues, shaded residential

streets. Obvious redevelopment is underway with a small park by

the bridge, new brick sidewalks, and bright new historical markers.The

city has created a historic walking tour based on the 1965 marches

and there is a Voting Rights Museum.

|

| I took the walking tour which went down one side of King Street

a few blocks and back on the other side with information kiosks

every fifty yards - I walked by the George Washington Carver Housing

Complex (where civil rights workers trained and were housed),

Tabernacle Baptist (where the first mass meeting was held after

the ban), Brown AME chapel where King spoke, the alley which became

known as the Berlin Wall when police roped it off. Afterward I

walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. |

Housing Project

|

Selma

|

Why Selma? The city has been at the forefront of black activism

SINCE THE CIVIL WAR. In 1867 Selma had a black policeman. The

first black congressman in the nation (Benjamin S. Turner) was

elected from Selma in 1870, followed by Representative Jeremiah

Haralson in 1874 (who later became the first black Republican

National committeeman). The county elected a black judge in 1874.

The first African Methodist church in Alabama is in Selma, and

several black colleges. The county had a large number of black

voters in the late nineteenth century. Then in 1901 the Alabama

legislature greatly limited voting eligibility and the number

of registered black voters in Dallas County declined from 9871

to 52 (!) . That was really the beginning of the Voting Rights

Movement. |

| The Dallas County Voters League (DCVL) was established in the

1930’s and its board kept the pressure on officials. In 1963 SNCC

came into Selma to help with voter registration. Mass meetings

were held. In July a local judge prohibited all mass meetings.

The DCVL invited Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership

Council (SCLC) to help. On January 2, 1965, Dr. King defied the

judge’s order with a mass meeting at Brown AME church and marches

were planned. Three marches took place in Selma, the third culminating

in the walk from Selma to Birmingham. During the First march on

March 7, 500 protester were met at the bridge by gungho Sheriff

Clark and his cops. When the crowd was ordered to disperse and

didn’t, the cops attacked and 65 people were injured. Dr. King

called a ministers’ walk for March 9th. It was turned back. Increasing

media attention focused on the city. On Sunday March 21, 3000

marchers successfully crossed the Pettus bridge. 300 continued

on to Montgomery and arrived there five days later. |

Brown Chapel

|

“Selma Alabama became a shining moment in the conscience of man”

- Martin Luther King Jr.

We left Selma by the Pettus bridge and drove the fifty miles to

Montgomery, following the route the marchers had taken in 1965.

I had no image of the actual road and found that it is beautiful,

The highway is divided and goes through rolling green farm lands.

Montgomery is a gutted city, razed by urban redevelopment. Decaying

neighborhoods greeted us, then wide empty boulevards and vacant

lots and spanking clean government buildings. Montgomery was quiet

and empty on a Sunday afternoon. We easily found the heart of

the city: the huge imposing domed state capital with Martin Luther

King’s brick Dexter Street church right across the street ! I

had no idea. King’s church is as close to the capital steps as

Blaine House is to the Maine statehouse! What a thorn in the side

of the segregationists in government Dr. King must have been.

It is not obvious today where Dr. King’s congregation came from.

There is no neighborhood near to the Dexter Street church today.

| The Civil Rights monument is only a block away, in front of the

Southern Poverty Law Center. Maya Lin designed a round black marble

“table” inscribed with the names of all who died in the modern

Civil Rights Movement. The table is an off center cone with its

apex in the ground. Water flows evenly from the center of the

table to the edge and then surface tension holds it under and

down the undercut slope. Behind the table a wall of water washed

a quote from Dr. King. Both images (table and water) have Biblical

allusions. The monument is smaller than I expected, human scale,

very beautiful. White teenagers from a Praise Shout Choral Tour

were dabbling their hands in the fountain. |

Civil Rights Monument

|

Montgomery also had a long tradition of active protesters. A women’s

group had been working for civil rights and Rosa Parks was part

of the local NAACP. In 1955 young Martin Luther King Jr. became

minister of the Dexter Street Church. When Rosa Parks refused

to give up her seat in the front of a Montgomery bus to a white

man, and was arrested, King helped organize the Montgomery bus

boycott. It lasted almost a year.

The bald facts (marches turned back, a one-year boycott) don’t

convey the feelings and hardships of those involved. A minister

from Boston (James Reeb) was beaten to death in Selma, a young

man (Jimmie Lee Jackson) and a woman protester from Detroit (Viola

Liuzzo) were shot. Many others were injured by police clubs -

broken bones, huge bruises, heads cracked open, pain. In Montgomery

blacks organized car pools and walked long distances to and from

work. Some workers had to leave home before dawn to make their

commute. The summer heat in Alabama on a three mile walk after

a full workday must have been devastating, but the boycott endured.

Memorial

The outcomes of Montgomery? The buses were integrated, followed

(during the protest years) by restaurants and pools and stores

and motels. Driving through the South today you are not aware

of segregation except in the distinct residential neighborhoods.

The outcome of Selma? In 1965 President Lyndon Johnson signed

the Voting Rights Act to guarantee suffrage to citizens. A 1968

Act reinforced the broad Civil Rights Act of 1964 barring discrimination

in employment and public accommodations. Sheriff Clark was defeated

in the 1966 election. In 1972 blacks were on the Selma City Council

and in 1988 blacks had the majority of seats on the Selma County

Commission. Selma tourist information lauds the black history

of the city and the Historic Walking Tour of the voting rights

movement is the best marked area we’ve seen in Alabama. Traveling

through the South shows a publicly integrated society.

We had one last stop which added to our picture of the civil rights

struggle. Thirty miles east of Montgomery is Tuskegee University,

the black university established by Booker T. Washington. Washington

is a controversial figure today because he accepted the notion

of “gradualism” (slow integration) and trained black for vocational

trades. Yet the university he established seems to be the center

of a strong black professional community. The campus is huge and

beautiful, brick buildings dot the hills and winding paths link

them. There are huge shade trees and lawns and small ponds. Construction

is going on in several parts of the campus. The buildings show

the breadth of curriculum from the liberal arts to education and

forestry. It looks like any large liberal arts college. Every

adult and coed, every storekeeper we saw in Tuskegee was black.

My first teaching experience was at Hampton University, a black

college in Hampton, Virginia, where I became aware of the ease

there is for minorities in a minority dominated school, where

the role models are mostly black and the campus organizations

are run by blacks. The traditional black schools (Vanderbilt,

Spellman, many A&Ms, Hampton, Tuskegee) have gone through cycles

of change. Since the 1960’s, black academics and high school stars

have been courted by white universities, but Tuskegee and Hampton

(which we revisited in Virginia) show that black colleges are

very much alive today. They may be the strongest training centers

for black professionals and political leaders.

Selma, Montgomery, Tuskegee. We ended the day with a feeling of

hope.

4/6.. contd.

We beat feet.. or wings. Got swept up onto the interstate, and downloaded immediately

at a fresh produce mart. Scanned in some veggies and fruit. Local

vine ripe tomatoes in April. They say that it gets too hot after

May for tomatoes, if you can believe it. Then we ambled along

byways to Tuskeegee.

Tuskeegee is a big University, sprawling down a wooded ridge,

and busy with new construction on its margins. The Booker T. Washington

Museum was closed, naturally, in the Sunday style, but Booker

has been badly debunked since he was the hero of our PC texts

in the 50s. Favored gradualism and trade school education... all

that stuff that got Xed by Malcolm.

The Owl fluttered around and about the campus.. basic college

scene, except totally black. Peggy has been taking van-loads of

prospective students on college tours for years, and has a keen

eye for institutional detail. She was impressed by the depth of

facilities, and smiled at the frat houses and sororities.

High speedbumps made our springs squeak, and the maze of roadways

kept ending at a locked gate. As usual I ignored the Thou Shalt

Nots and squeezed down sidewalks and byways, only to be foiled

at every turn. Began to turn a little pink when the undergrads

started watching us closely. I started to suspect the labyrinth

was designed to confuse hostile invasions. Like the Brits removing

all the roadsigns during WWII.

We made it to Dunkirk, and proceeded toward the Georgia line.

Another indepth state tour: Alabama in 60 hours. Lilian to Phenix

City. If our snoop gives good poop, the Heart of Dixie could steal

yours, in April. The most beautiful country we’ve seen since leaving

Maine, this time.

Our pit stop at sabbath’s end was in Columbus, Georgia, close

to the sports complex: 5 (?) stadia all clumped together. I felt

so athletic I went walking along the riverside amenity, which

runs for 18 miles. I didn’t, but enjoyed ambling beside the Chattahoochee,

with folks fishing on the sandy margin, cyclists whizzing past,

and fellow walkers inhaling the thick sweet fragrance of the chinaberry

trees in bloom. Millions of little purple flowers, whose first

whiff reminds you of some flavored pipe tobacco, then the full

fruity aroma floods your blood sugar. I went back to the cabana

where Peggy was doing laps and waved the checkered flag at her.