American Sabbatical 64: 3/5/97

Lowell

3/5.. Stuffed Owl.

The dogs knew we were leaving before we started packing. It’s that orphaned look they give

you. So you’re abandoning us again, it says. And they plant themselves

in your path, doleful eyes watching every move. Yes, we’re taking

flight again, doggies.

Stuffing the Owl was a piece of cake this time. We’d radically

thinned our kit, and everything has its place. But the thousand

and one things you suddenly remember just before you leave get

you running around the house in circles, a departure ritual which

culminates in two crazed humans tripping over hovering hangdogs

and bumping into each other.

Seven o’clock Tuesday night I decided to fix the leaking toilet

tank so our house sitters wouldn’t have to deal with it. Just

a simple job of replacing the stopper mechanism. A nice practical

task to clear my head. An hour later I was lying on the bathroom

floor with my fingers jammed under the tank, trying to loosen

a stuck nut, with the tailpiece pipe twisted in a spiral, and

near tears with frustration.

Mr. Mann to the rescue. David arrived to see us off, and stayed

to play plumber. Went home for his big channel locks, and returned

with a full tool box. Just in case. Well.. we needed it. His big

calming presence was the best tool in the box, though. It only

took us three tries to get the works apart and together again

so it didn’t gush, and I would have left the damned thing oozing

and gone off in despair but for David’s patience.

By the time we were replumbed, Peggy had fallen down in exhaustion,

but I was running in overdrive. Time for a symbolic finale. The

tail on Peggy’s dolphin totem had broken off Saturday, and the

piece gone missing, so I decided to repair it. But the wood has

acquired such a patina after 20 years of rubbing there was no

way I could match it. I couldn’t even tell what species it was,

it had such a glow. The only solution was to make a whole new

dolphin. I chose osage orange for its golden color, jacked Bob

Dylan’s Slow Train Coming into the sound machine, and began the

shop dance. By midnight I was holding a golden dolphin, and things

were back together again. Bryce’s ultimate therapy.

The big storm that media central was promising hadn’t moved in

by morning, and the last bits of stuffing went into Red Owl without

mishap. By then we were both in a transitional trance. Neither

here nor there, and grinning foolishly. Peggy went through the

house blessing the rooms, and I hugged the dogs, confirming their

worst fears. And we were off.

Almost. Leo’s ashes were waiting for us at the post office, and

we had to backtrack to put them together with Zimi’s at home.

One last sad office, marking another completion. Then we were

OFF.

3/5-6...Outastate.

We chose to amble out of state, rather than take the fast lane and get all jangled right up

front. So we went crosslots to Lisbon Falls, crossed the Androscoggin

at the old Worumbo, and picked up Rt.9, a little shaky, but away.

Old Route Nine is Maine’s back alley, and in summer it’s an education

in lawn ornamention to drive along its bluecollar miles. This

time of year Maine shows all its scars in a sea of drab, and 9

bobs and weaves through Pownal and Durham, Cumberland and Yarmouth,

unrolling a study in beige. Crossroads meetinghouses and town

commons are intercut with logging yards and frozen pastures. There

were still patches of snow on the ground in Bowdoinham, but the

landscape was bare as we came down onto the coastal plain at Portland.

There are some wonderful 19th century houses on the back streets

of Portland and a whiff of salt air stalks along the avenues.

We snaked across town under a pale blue sky, with our windows

halfcocked, made an endrun past the Maine Mall, bemused by the

eager morning consumers, and dumped out onto Route 1 south, the

old commercial corridor. Buyers were out kicking tires at Jolly

John’s, and you could almost hear his hustler’s gush in the air.

YEAESSS.

The traffic was only moderately heavy, with fish dealer and lumber

company trucks huffing diesel across Scarborough marsh, and past

the shuttered motel cabins inland from Old Orchard Beach. Is this

really the last place in Maine where strings of efficiency cabins

turn back the clock to the 50’s. Do Mom and Buddy and Sis still

drive up in their DeSoto for a week in August? I hadn’t driven

Route 1 between Scarborough and Wells since they put in the Maine

Turnpike, and if you squinted your eyes it was still the 1950s..

But what happened to ESSO? And what’s a calzone? Or an Aquaboggin?

Biddeford-Saco is a living milltown, with plumes of fumes pouring

across the winter streets from the looming factories, girls in

curlers and fuzzypink slippers on the stoops, smoking menthols,

and all that triple-decker ambiance. Only the storefront signs

said 1990’s: GET ONLINE HERE. YOUR ONRAMP TO THE INFORMATION HIWAY.

You suppose Dolly works in an information factory?

We cut inland, through the cutover pine plains of York County,

in order to cross the Piscataquis at Berwick, and backdoor out

of Maine. Berwick is another for-real milltown hunched alongside

the waterpower, with worn faces on the buildings and the residents.

Across the cast iron divide and into New Hampshire, we eagerly

looked for signs. Indications of the rugged independence of these

Granite State survivors. These primary voters who do such a fine

job of choosing our candidates. This is LIVE FREE OR DIE country.

Only it was hard to tell which was the operative modality. The

road signs gave out at the town line, and we figured out that

no taxes and political independence means: figure it out yourself.

We stopped to ask directions from a cop directing traffic, and

he just shrugged. Lucky we had a compass.

After circling round for most of an hour we finally came upon

the State Youth Center, and realized the logic behind no road

signs. That’ll fool them. We eventually struck on a numbered route,

and hightailed it for the Mass. line. The ceiling was coming down

sooty gray, and we had our windows rolled back up. By the time

we came into the stop-and-go of Haverhill we’d had enough scenic

touring, and were ready for the thrill of the high road.

You get as many thrills as you want in Massachusetts traffic.

And I’ve finally figured out what defines the special charm of

the Mass. driver. They have their own sense of proxemics.. IE:

they crowd in on you. This may be the Fenway Effect. All those

old serpentine roadways, coupled with a long tradition of road

construction graft, means there are no lane markings and other

orderly amenities, and driving in Boston is a free-for-all. Two

lanes become three then one, merges diverge and converge, the

result is a casual attitude toward lane discipline, which drives

the rest of us nuts.

Now the same logic would argue that New Yorkers should suffer

from the Bruckner Boulevard Effect, but Empire Staters are rigidly

regular in their automotive mayhem. I think the difference is

the pace. In the Big Apple you’re dead if you break the pattern,

because some crazed cabby from Peshawar is doing 85 in the next

lane. In the Hub there are so many hungover Irishmen hanging a

U-ey that a general casualness prevails. This may explain the

Bay State’s liberal politics, as well.

In any event we played dodgem with Mass....s all the way to the

Lowell Connector. Peggy wanted to sniff around the Mill Museum

in Lowell, and we rolled into that historic district in mid-afternoon,

with a raw wind rising.

Lowell is a city of brick and granite blocks where the side streets

are still cobbled, and a nineteenth century atmosphere hides in

the alleyways. There is a National Historic Site in the city center

where the old mills stand shoulder to shoulder. But the sense

of time past is tempered by flocks of kids, whose families are

living in the converted factory buildings. Lots of young trees,

fresh glazing, and new paint. The laughter of playing children

echoes in the brick courtyards.

(Memo #53)

March 5 - Lowell National Historical Park / Industrial History

Who? Francis Cabot Lowell, millowners, millworkers, immigrants

What? First industrial city in the USA. Mills, mill housing along

a river and canals. Mass production.

Where? Lowell, Mass., on the Merrimack River.

When? Beginning in 1810, fast urban development. with distinct

stages - farm girls first, then immigrants.

How? Labor, capital, machines, resources, workers, transportation

were put together in the famous “American Factory System.”

|

Lowell Mill

|

|

Topics: the Industrial Revolution, the American factory system,

urbanization, mass production, millworkers, labor unions.

Questions: Why did the mills develop where they did? What were

the earliest mills like? Who were the workers? How did mill conditions

change over time? |

|

|

If you take Route 495 southwest from Route 95 just out of Maine,

you begin to see signs for the old industrial cities of Massachusetts

- Lawrence and Lowell. Then the old mills themselves appear by

the river off to your right - huge brick structures that run for

miles, it seems, along the waterfront. The huge empty rooms where

looms once throbbed can be glimpsed through the ranks of windows

that line five or six stories and stretch into the distance. The

mill chimneys loom over all, higher than the clock towers at the

central mill entrances. The few pedestrians and cars to be seen

are dwarfed by the brick giants. It is an impressive geometric

manmade urbanscape.

|

| The road signs advertise the Lowell National Historical Park which

chronicles the development of the American industrial revolution

at its first urban sites. This chapter in history left its mark

near Freeport with the huge mills at Lisbon Falls, Lewiston, Waterville,

Rumford, Brunswick, and the cities created by and for the millworkers.

Fire destroyed the mill at Lisbon Falls, decay is attacking the

yellow mill at Brunswick. It is a contemporary challenge to restore

and use the great mill structures. Lewiston has restored the Bates

Mill for new functions (an arts center, a photography enterprise).

Fort Andross in Brunswick houses a restaurant, auction house,

ski business. Lowell has become a huge national park. So, on our

first day out on Trip # 2, we headed for Lowell, Massachusetts.

Could this nearby National Park be the center of an American Studies

trip some day? |

Lowell Clock Tower

|

Lowell has new “mill housing” on its outskirts, serried ranks

of condos (that are really row houses) marching up hills and along

side streets. There are large empty lots dotting the downtown

and a few grand stone buildings endowed by the mill owners (a

library, a city hall). Then you are alongside a mill canal with

the great brick mill buildings and their chimneys (the park has

fifteen major sites on a map).

Sculpture

|

Lowell National Historical park is not one reconstructed mill

but a whole huge section of the old downtown. From the visitors

center, it was a fifteen minute walk to the Boott Cotton Mills

through cobbled streets with sandblasted brick stores and mill

structures. There is a walking path along the old canal and vest

pocket parks with sculptures memorializing industrial development

sprinkled throughout downtown. One lifesized statue of a millworker

is levering a huge granite block. Cogs from the huge machinery

are set up as art pieces.There are also antique stores and natty

restaurants. Downtown was really attractive (Lowell?!?##@#). |

| So, why Lowell? The industrial Revolution was a change in the

way things were produced that affected every aspect of life -

how and where people lived, how they worked, what they worked

for. Before the Industrial Revolution things were made at home.

A craftsman like a potter or a weaver or a blacksmith worked in

a room of the house or a building out back. The production involved

the whole family - kids would run errands and do small chores,

then get trained in the family craft. Women had important economic

roles doing craftwork and bookkeeping as part of a family enterprise.

The objects were made one at a time, usually by a single worker.

Each was slightly different from the other. |

Canal

|

Mills

|

Work and family and home were integrated. Objects produced might

be bartered as part of a network of goods and services in a village.

Cities were trade centers where transportation routes came together

and goods were marketed; ceremonial centers where religious events

occurred; government centers where officials worked. Work was

done by human labor, animal labor, and natural forces - wind turned

grist mills, horses pulled plows, camels carried burdens. |

| The Industrial Revolution used new energy for new purposes and

changed the landscape. Waterfalls (and later fossil fuels) were

used to power huge machines that increased production a thousandfold.

Machines were housed in huge new structures called factories.

These factory building complexes (mills) located at waterfalls

became the center of new huge settlements (Lewiston, Brunswick,

Lisbon Falls, Lowell). Workers lived within walking distance of

the mills in new kinds of houses that were part of the growing

industrial cities. There was a separation of family/home and work.

Work became a new kind of labor: wagework in a factory for an

owner. Your labor earned you money in wages and the millworker

was a wageworker and consumer, not a small businessman and barterer.

Objects were produced by the thousands, virtually identical. The

millworker did one task as part of this mass production. No one

was involved in the entire process from raw material to crafted

object. |

Chimneys

|

The mills required huge amounts of resources, bulk raw materials

had to be moved to the mill and finished goods had to be shipped

out. Canals and railroads were created as the transportation part

of the industrial revolution. The “American Factory System” emerged.

Boarding Houses

|

The first great mill industry was textiles. Eli Whitney’s cotton

gin cleaned seeds from huge amount of raw cotton efficiently (ironically

the "advance" of the industrial revolution made slavery profitable),

boats carried the cotton bales to England, then later to the mills

of New England.

The Boott Cotton Mills complex at Lowell stretches for hundreds

of yards alongside the Merrimack River just before the Concord

River joins it. A huge open square in front gives you a grand

view. Along one side of the square are restored boarding houses.

I toured one, fascinated by the life it depicted. |

The first U.S.mills in the early 1800s (England was earlier) had

to attract laborers from farms and small villages. The millowners

offered good wages and conditions at first. The mills were fairly

light and comfortable. Farm girls by the thousands came to work.

New cities were "springing up like enchanted palaces" (Whittier).

Lowell was described as the "eldorado on the Merrimack." By 1850

Lowell had 33,000 people. At first the workers were mainly women

between 15 and 30. The average stay was three years. Workers toiled

73 hour weeks and earned $3 a week.

|

Dining Room in Boarding House

|

Loom Operator

|

At Lowell, twenty-five to forty girls lived in each boardinghouse.

Their voices (readings from diaries) follow you as you tour the

narrow brick row house - three or four stories high. The boardinghouse

diningroom is a large room with many tables. The “keeper’s room”

(bed and sitting area) is just behind it. The keepers were often

widows or single women with multiple business skills. The keepers

competed with good food and comfortable rooms to lure boarders.

Typical meals are displayed shellacked (!!). Upstairs was a typical

dormitory room for several girls with beds lining one wall. Exhibits

in an adjacent house showed aspects of the entertainment, religion,

and cultural events that were offered in evening classes and lectures. |

| What changed? Why did factory life and mill conditions deteriorate?

As long as labor was scarce in the U.S., mill conditions were

good. The great waves of immigration provided an abundant labor

force (first the Irish fleeing the potato famine and French-Canadians

fleeing farm poverty, then eastern and southern Europeans, more

recently Asians and Latin Americans ). The workers didn’t have

to be kept happy, there were always more workers (men and women

and children). Wages dropped, conditions worsened. Hours increased.

Profits soared. In the 1830’s Lowell had its first strikes, the

beginning of the labor movement that has been an integral part

of Lowell’s history and is chronicled in many history books .

Reformers like Sarah Bagley and Harriet Jane Hanson Robinson lead

worker protests and sent petitions to the government. The city

began to have ethnic neighborhoods (New Dublin, the Acre) with

special restaurants and stores. Many languages were spoken. Exhibition

photos of Lowell show signs in Greek, Italian, Russian. Artifacts

brought from Rumania or Germany line cases. |

Mill Model

|

Looms

|

The Boott Mill complex recreates the working environment in the

1920’s. There are 88 power looms set up in a huge mill space weaving

the different types of cloth once marketed by Boott Mills. Tourists

are issued earplugs and walk through the noisy room. It was deafening.

In the 1920’s the rooms would have had twice as many looms (!).

Diaries describe the dust and cotton particles in the air (mill

workers typically developed respiratory problems). Upstairs where

the floor throbbed from the looms underneath, there was an excellent

slide show and exhibits of everything from millworker clothing

to an authentic cotton bale (its 500 lbs. from 25-30,000 bolls

could produce 1500 yards of material). In 1839 Lowell mills used

890 bales PER WEEK.

|

| At Lowell, tourists can see an extensive water turbine power exhibit,

the cotton mills, boardinghouses, transportation museum. You can

walk the downtown or take a boat ride on a mill canal. The mill

town experience is extremely vivid. VISIT !! |

Millrace

|

3/5 cont.

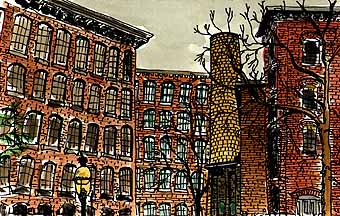

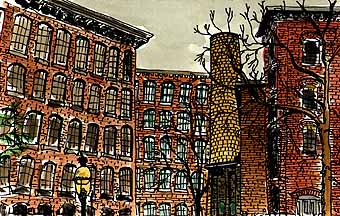

While Peggy did her museum thing, I leaned against a wall and sketched a yellow brick chimney

towering over a mill yard. A young Hispanic boy and his rotund

father were passing a football up and down the alley, and an older

Irishman joined the game. Pretty soon there was a gaggle of kids

surging back and forth. The young boy came and looked over my

shoulder, shouted excitedly in Spanish to his dad, and in a minute

I was surrounded with eager critics. Talking to each other in

Spanish, and (politely) to me in English, they discussed the utility

and economic value of art.

Bryce's Lowell

“How much can you make doing this?”

One young lady said they had just cut out art at her school. “They

don’t think it’s very important.” I said it was important to me,

and she said softly, “Me too.”

“Can you do this with crayons?” she asked. I said she should use

anything she can lay her hands on.

When I gathered up my kit, the father came and shook my hand.

“It’s important my children see all the things you can do in this

life.” Is this country a hostile place, full of racial hatred

and urban violence? A place where people have no time for art?

I rest my case.

Even on a lowery evening this tired old mill town had a rough

charm I’d never have associated with the Merrimack Valley, and

Peggy was all abubble with field trip possibilities and student

projects she could envision. The sabbatical thing sure hotwires

this jaded teacherlady. We munched on fresh bread and exotic cheese

as we pulled back out onto the road, and into the coming weather.

By the time we struck Sturbridge it was pouring, and by Hartford

it was pitch black. We felt our way across western Connecticut

and up into the rolling hills, headed for Kent and Cornwall Bridge.

Luckily we knew our way around these woods, because there was

fog in the valleys, and intermittent bands of hail dancing on

the macadam. Even so we made a few false turns and had to circle

the wagon and regroup.

We were aiming for the home and studio of Lois and Herb Abrams.

Herb has known me all my life, and been a crucial inspiration

for me as an artist. He is a successful portrait painter (White

House portraits of Carter and Bush), who has followed his muse

through thick and thin for 50 years. Herb went to high school

with my father, and lived with us during my childhood. I grew

up in a house full of his paintings, watched his talent evolve,

and can't smell oil paints without thinking of him. His stubborn

climb to success has always been a model for me, but it has been

years since we visited him at home. When we finally appeared out

of the deluge, with a package of lobsters under our arm, we were

welcomed like a prodigal son... and daughter. Maybe it was because

everyone was starving.

Mellow scotch, fresh shellfish, vintage wine, fancy applecake,

aged brandy... we tottered off to bed convinced that this artistic

life is definitely the way to go.