American Sabbatical 031: 10/13/96

First Peoples

10/13.. First Peoples.

|

Then it rained. I mean RAINED. They don’t call this rain forest for nothing.

Which explains the waist-high bracken, the inches of moss on everything,

the spongy bounce of the ground underfoot, and the saturated intensity

of the greens. British Columbia is very British in its verdant

lushness. Where else would alders grow a hundred feet tall (and

make good firewood)? Where would arbutus stop being a climbing

shrub and become trees four foot across the butt? Where else would

maples have leaves a foot wide?

|

| Our spirits weren’t dampened, though. We walked the shoreline

and the high woods in the descending drip, and played with the

donkeys. Much of the beach was solid white clamshells from old

Indian middens, and the driftwood would break a log scavengers

heart. The coves of the islands are filled with rafts of Doug

fir, ready to be towed to the mill, and the beaches are littered

with the remains of gypo logging gone adrift. |

Spirits

(Bryce)

|

Kwagiulth woman 1897

(Benjamin Leeson photo)

|

Through the blowing mist, black mountains played hide-and-seek,

and the white streamers of stormclouds hung on the peaks, or slid

between the islands, reshaping the landscape. The big ferries

winding between the islands blew their evocative tunes, and the

donkeys honked in key.

|

We got so unwound our clocks stopped, and Kelly had to chivvy

us up on Sunday morning to catch the predawn ferry. It was Thanksgiving

weekend in Canada, and we had to decamp then, or stay through

till Tuesday. And we didn’t want to butt into the family holiday,

even though we were invited. We did visit Ruby, Kelly’s mom, who

raises horses at 78, and had a big turkey dinner with Kelly and

friends at the local bistro. But it was time to come ashore.

When we rolled onto the Princess of Nanaimo in the thin gray dawning

it was still pouring intermittently. But by the time we nosed

into the slip at Tsawassen the black mountains across the Strait

of Georgia were humped up in line along the southwest horizon,

and the drizzle came and went. |

Call Home

(Bryce)

|

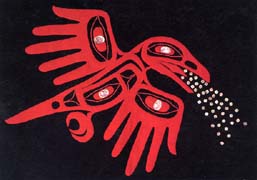

Raven

(Bryce)

|

We followed the flow into Vancouver, a beautiful city straddling

inlets beneath a mountain backdrop. We only caught glimpses of

the panorama, crossing the Oak Street Bridge from the west, as

dense white cloudbanks dodged among the hulking orogenics to the

east, but what we saw was impressive. We had been directed to

Stanley Park as worth the looksee, so we crossed through the city

and onto the park peninsula. Here was a bit of Mt. Desert and

Acadia, in downtown. First-growth rain forest rising onto high

bluffs, with serpentine walking and driving trails, in the heart

of a major city.

|

| We made the full loop, craning our necks to sight the tops of

the big cedars and firs. Then we aimed Festiva for Granville Island,

the city produce market and arcade on a separate islet in the

stream. Contemporary northwest art, buskers singing blues and

two-part ballads, exotic cheeses, mountains of fruit and veggies,

the lure of tempting scents, delis, bakeries, and a Sunday crowd

of Vancouverites bumping and ‘scusing. Yum. |

Stone & Antler

(Bryce)

|

Yacht Condos

|

What is it that defines a Canadian ambiance? There’s a bit-of-a

lilt to the lingo, A? And a kind of well-washed wholesomeness,

youknow. The Northerners we know are anything but bland, and yet,

the culture borders on the soporific. Is it that Canadians don’t

push their egos at you (unless they are headed south to fame and

fortune)? When you bump into Americans (“Yankees”) in Canada they

seem aggressive, loud, often overbearing. On the other hand, Canadians

often need amplification to be heard. |

| In Vancouver the mix is a bit livelier. It’s a very oriental town.

They say Hong Kong is resettling among the already numerous oriental

population of the Banana belt. And the place looks like I’d imagined

Hong Kong. The mountains and waters, the highrise housing. And

most of the highrise in Vancouver is apartment buildings, with

a thousand flying balconies to catch the views. This is a downtown

that is lived-in, and the pedestrian liveliness makes it a very

human town. |

Inuit Carving

(Bryce)

|

Water Taxi

|

It’s also a gardener’s delight. Anything and everything will grow,

so every niche and crevice bulges with hedges and flowers and

hanging greenery. Here are water-taxis dodging yachts alongside

condos dripping grapevines. The Canadian affect may be flat, but

the effect of Vancouver is enticing. |

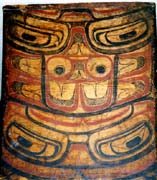

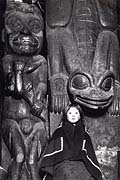

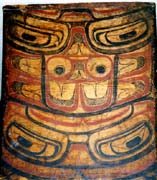

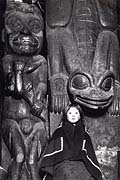

| We slethered around to the Museum of Man at UBC, and caught a

heavy dose of indigenous culture. This anthropology museum has

a knockout collection of northwest coast carvings, from 60-foot

totem poles to handheld fetishes, carved canoes to inlaid masks.

Not only are the major displays a jaw-dropper, but the entire

collection is available for inspection, in drawers and cases,

so you can be overwhelmed in the minutest detail, at your will.

The whole range is there, from the hilarious to the majestic,

from pocket magic to the monumental. The undercurrent of violence

in the cultures wasn’t suppressed. As Peggy said, “Reality isn’t

romanticized here, only idealized.” We went outside and stood

in the rain, now pouring again, next to the totempoles, and looked

out onto the foggy mountains. It wasn’t romantic at all, but evocative

as an owlcry. |

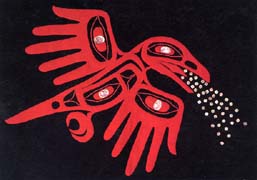

Raven Dancer

(Bryce)

|

And here we are. Turning a corner on the trail. Up among the totempoles

in the rain forest, and looking for a roadsign. Maybe it’s time

to make a symbolic gesture. When we set out we tied an owl mask

Peggy had painted (on leather, in northwest coast style) to the

rearview mirror of Festiva. There are three faces peering forward

through our windshield. On Galiano, as far west as it gets, we

were met by a big owl in the tall timber. Maybe our fourwheeled

traveling companion has earned a magic name. Let’s call her RED

OWL. oooHOO!

Owl

Now it’s time to get back on the American path, A? So we pointed

Red Owl south. But it’s hard to find the road again. We have been

going WEST, chasing history’s compass-heading. So what now? What

new discoveries are waiting to the south? And will they let us

back in to make them? We had to stand in line for an hour and

a half at the border, just to get re-enthused about the old USofA.

Ah INS.You don’t want to make it easy for northern aliens to get

in, do you? They might make America boring. We fumed in the cue

listening to moanful country on AM radio, watching the sun try

and come out over the Olympic peninsula. When we finally got to

the gate it was “Maine,eh?” and a jerk of the head. Great to be

back. oooHoo.

(Memo #29)

Oct. 13 - Northwest Cultures Museum

Who? Native Americans/First People of Northwest Coast (Tsimshian,

Bella Coola, Kwakiutl, Tlingit etcetera)

What? museum of their rich material culture

Where? overlooking Vancouver Harbor

When? today

How? University of British Columbia collection

Topics: Northwest coast cultures.

Questions: What is tradition?

|

Kwagiulth Wedding Party

(Edward Curtis 1914)

|

Chief's Daughter 1914

(Edward Curtis Photo)

|

The Tlingit, Tsimshian, Nootka, Bella Coola,and Haida are some

of the Native American groups of the northwest coast of North

America. What everyone knows of them is their totem poles, the

huge elaborately carved wooden posts that were set up outside

the houses. That is appropriate, since wood was their primary

medium and carving the glory of their rich material culture. As

a contemporary Haida artist puts it -“Art is our only written language.” |

| In Canada these groups are being called the “First Nations” or

“First Peoples” (terms which seem more appropriate to me than

“Indians” or the PC “Native Americans,” since many of us are native

Americans - i.e. born in America). Although decimated in the nineteenth

century by warfare and disease, these peoples have endured, and

the population has grown recently to some 169,000 people who,

like their Yankee counterparts, live in cities and towns, or on

reserves created by the Canadian government (similar to reservations

in the USA). |

Bella Coola Big House 1898

(Edward Dossetter Photo)

|

Great Bird

|

The peoples of the Northwest coast are puzzles in some ways to

Anthropologists. They do not fit the categories. They were sedentary

village peoples, although they had no agriculture. They were technically

“hunters and gatherers” relying on wild plants and wild animals.

The foods of the northwest coast were so plentiful that these

modern day hunter-gatherers were NOT nomadic. They lived in villages

of huge planked post-and-beam wooden houses, lined up on the beaches,

and ventured away to fish and hunt and gather plants, roots, and

berries from the forests and the sea. They could and did accumulate

great material wealth. |

| Their environment provided huge trees, and they became master

carvers of poles and boats and boxes and trays and masks and jewelry.

Copper was the key metal used before trade brought them gold and

silver. The women wove baskets and robes. They developed a very

distinctive artistic style - humans and animals and mythological

creatures are rendered in bold curvilinear form, in vivid colors,

with heavy black outlines. |

Northwest Styling

|

Tswawadi

(Carpenter Photo)

|

Their society had complex class and rank divisions, and an elaborate

ceremonial system. A key ritual that puzzled Europeans was the

potlatch, a giving away or destruction of huge quantities of goods

which might beggar the host, at the same time it brought him greatly

increased status. Europeans tend to GET goods when they marry

or have children or celebrate rites of passage, and see material

wealth as something to be hoarded. |

| The Museum of Anthropology of the University of British Columbia

is a tribute to the Northwest coast peoples. It is on a fabulous

site in a grove high over the harbor of Vancouver with dark mountains

in the distance. The building was designed using elements of their

art - heavy lintels and upright posts. Contemporary artists of

the First Nations carved the wooden door panels. Inside huge carvings,

boats, and totem poles are set up in the soaring glasswalled great

hall. |

Frog Clan Totem

(Winter and Pond Photo)

|

Hands of Creation

Contemporary

(by Beau Dick)

|

A super feature of the museum is the illustrations found near

every object that show where it was in a house or village. A panel

of carved birds is identified as part of a house’s wall decor,

and the illustration shows the house interior with the panel on

the wall, and with people going about their everyday tasks. Smaller

galleries hold jewelry, dress, masks. |

| Perhaps the most incredible feature of the museum is its open

storage. The entire museum collection is housed in glassfronted

cases and drawers. Any visitor can browse. You are not limited

to the small number of objects on official display in the public

galleries as you are in all other museums I know. In a great art

museum such as the Metropolitan you may only see one of the ten

oils they own by a particular artist. A curator puts together

an exhibition that s/he chooses. The viewer is, by definition,

limited to the curator’s choice. Moreover, objects may be out

on loan to other museums or exhibitions. |

Collection

|

Otter Rattle

(Haida 19th Century)

|

It is very frustrating to know that a museum has a dozen Monets

when only two can be seen. At the Chicago Art Institute in September

we were horrified to find that the ENTIRE American wing (over

six small galleries) which we had so anticipated seeing was closed.

Sorry. At this museum you can wander through the storage area

and see case after case of ritual masks or drums. And the collections’

catalogs are available in heavy notebooks that anyone can browse.

This really made it the first public museum in our journey. |

| The museum displays work by contemporary First Nations artists

which combine old methods and materials and subjects with new

ones. For example, the women of the Northwest Coast knit distinctive

heavy wool sweaters whose designs have the distinctive northwest

coast forms. First Nation jewelers are working in gold and silver

and bronze. I saw one mask that had a section made out of cardboard.

Many times native peoples are urged to produce only “traditional

art”. Tourists come to expect a certain color range or shapes

from a particular group. For example, tourists expect Navaho rugs

to be made in a certain fairly limited set of colors and styles;

Hopi pottery should be terracotta color with black designs. |

Button Blanket

(Tlingit 19th Century)

|

Missionary Carving

|

Why should native artists be handcuffed to a particular style

or motif? Why do we think that there was a single unchanging TRADITIONAL

style. Natives peoples have always changed though the centuries,

although modern contact certainly increased the pace of change.

After all, the Navaho didn’t start weaving until the Spaniards

brought in sheep, the Inuit (Eskimo) carvers prefer a stone brought

in from Wisconsin. An artist or craftsmen draws from her/his personal

and cultural background. This museum showed that First Nation

artists are doing the same. And the gift shops and city galleries

have new items using traditional forms - prints and belt buckles

and sandwich bags. |

“The only way tradition can be carried on is to keep inventing

new things”- Robert Davidson, Haida artist

Museum of Man